Infrastructure Financing through Islamic

Finance in the Islamic Countries

176

For Islamic banks, an additional problem is in the fact that in most countries their sizes are

relatively small. As such, they have a limited capacity to invest in large infrastructure projects.

Due to their small sizes, one option for Islamic banks is to provide project financing using

syndicated finance. Examples in which this has been done include the USD 50 million provided

by Islamic banks for the Master Wind Energy Limited project in Pakistan and the larger USD

422 million Doraleh Container Terminal Project financing done by Dubai Islamic Bank and

others in Djibouti. Since syndicated financing involving Islamic and conventional banks

requires complex contractual arrangements, there is a need to develop templates of contracts

to facilitate Islamic banks to finance infrastructure projects.

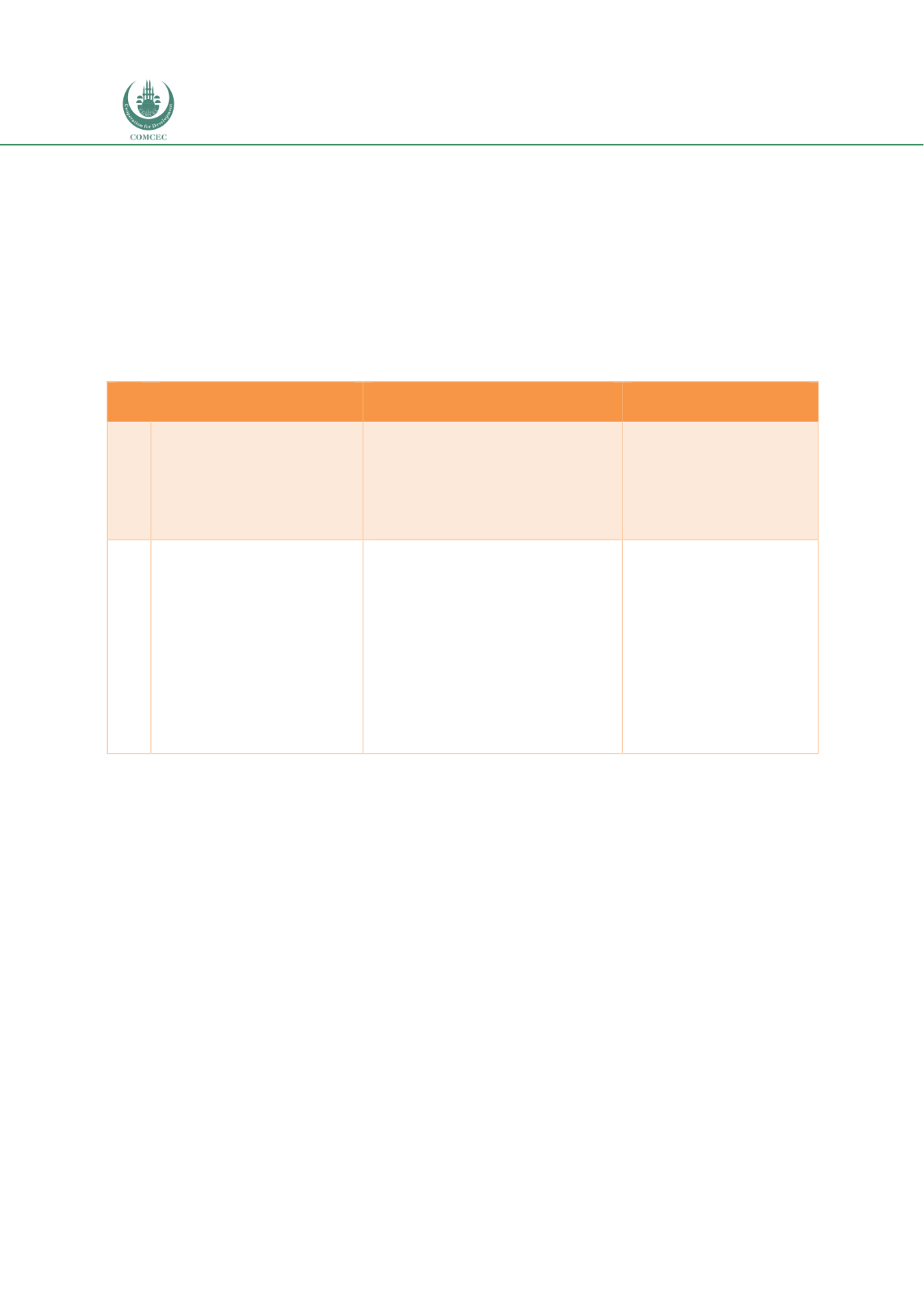

Table 5. 5: Policy Recommendations for Islamic Banks

No. Recommendations

Specific Steps

Implemented by

4.1 Increase Islamic banks’

roles in infrastructure

investments

Increase the share of

financing in infrastructure

projects

Develop long-term restricted

investment accounts

Invest in project

sukuk

Islamic banks

Regulatory bodies

4.2 Provide a better

supportive environment

for Islamic banks to

facilitate infrastructure

investments

Develop a well-functioning

Islamic money market

Develop templates of Shariah-

compliant contracts for

syndicated financing that

involve both Islamic and

conventional banks

Provide a better regulatory

framework for capital

requirements for

infrastructure investment

Industry players

Relevant

government

ministries

5.5.

Islamic Nonbank Financial Institutions

Other sources of finance for infrastructure finance can come from a variety of nonbank

financial institutions such as insurance/takaful, pension funds, and sovereign wealth funds.

Although the structure of the balance of family takaful companies makes it easier for them to

invest in long-term assets, the information on the asset distribution of takaful companies in the

countries examined in the study do not reveal specific information on the investments in the

infrastructure sector. For example, the bulk of the assets (43.7%) held by the takaful sector in

Sudan is in land and real estate, followed by bank deposits (29.6%), stocks (14.9%) and sukuk

(8.2%). While part of the sukuk issued by the government is likely to be used in infrastructure

projects, direct investments in the sector are not revealed in the data.

A key source of funds for infrastructure projects can be pension funds. While pension funds

exist in most countries, these are not Shariah-compliant. However, in some countries, parts of

the investments make use Shariah-compliant instruments. For example, 45% of the AUM

worth RM266.5 billion of Malaysia’s largest retirement fund EPF was Shariah-compliant in

2016, and Malaysia’s public services pension fund Kumpulan Wang Amanah Pencen (KWAP)