Improving Public Debt Management

In the OIC Member Countries

61

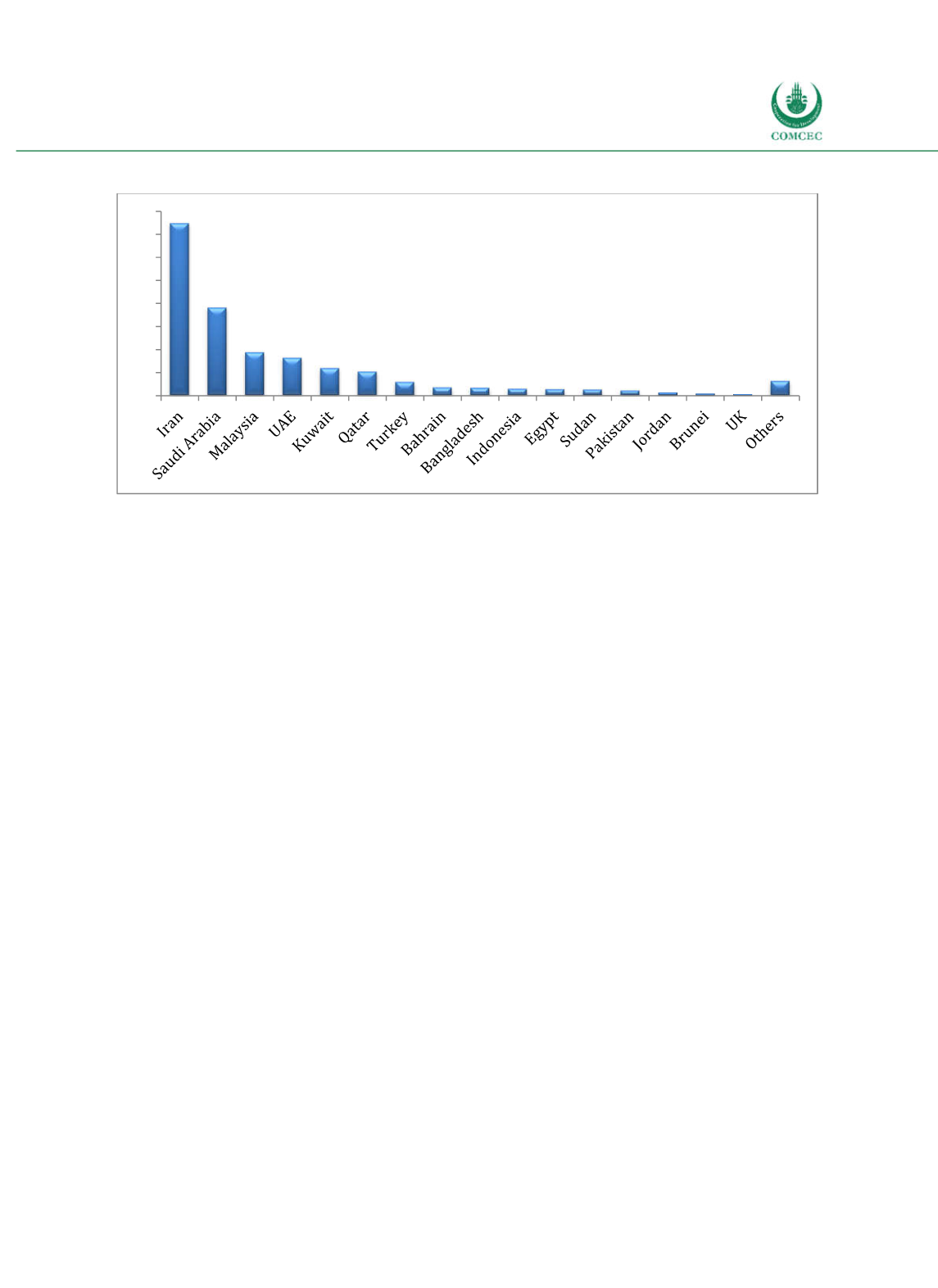

Figure 3-17: Shares of Global Islamic Banking Assets by Country (2015)

Source: IFSB (2016, p. 9).

3.3.2

Islamic Bonds

Sukuk

are private or public financial certificates commonly referred to as "

sharia

compliant"

bonds.

Sukuk

are defined by the Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial

Institutions (AAOIFI) as “certificates of equal value representing undivided shares in the

ownership of tangible assets, usufructs and services or (in the ownership of) the assets of

particular projects or special investment activity” (AAOIFI 2008). In contrast to common

bonds,

sukuk

do not pay interest. The investor rather acquires a share of the underlying project

that the

sukuk

bond is linked to. Investors either participate in profits in the form of equity

holdings of the underlying asset or project, or in other forms of profit and loss sharing that

yield flexible returns on the investment (

musharakah

). Another possibility is to earn fixed

income by receiving rental payments from the issuer, similar to leasing (

ijarah

), or by engaging

in a form of trust financing (

mudarabah

). At the end of the contract term, the issuer rebuys the

investor’s share of the asset at face value (Lewis and Algaoud 2001). Sovereign

sukuk

can be

connected to projects that yield an assessable rate of return, for example a factory or a trading

company (

mudarabah

), and to projects that do not yield a readily identifiable rate of return

such as, for example, schools (

ijarah

). In both cases, investors that buy the

sukuk

certificate

become coowners (see also Table G03 in the Glossary). Securities that allow investors to

participate in government revenues in return for their investment in public services are

another common funding instrument (Sundararajan et al 1998).

The first

sukuk

issuance by a government took place in 2002 in Malaysia and has become more

common since then (Jobst et al. 2008). Figure 318 illustrates the trend of increasing

sukuk

issuance. In 2012 and 2013 the highest amounts of

sukuk

issuance were observed. In 2014

sukuk

issuances slowed down and in 2015

sukuk

issuances dropped to $60.69 billion. The

decline in international

sukuk

in 2014 can partly be explained by uncertainties on the global

financial markets. Additionally, there were several longterm

sukuk

that matured in 2014 and

were not reissued. The major decline of total

sukuk

issuance in 2015 came from a decrease in

domestic

sukuk

caused by the decision of the Malaysian central bank – the most prolific issuer

of sovereign

sukuk

– to stop its shortterm liquidity management

sukuk

program (IIFM 2016).

Sukuk

issuance hit a record in the first quarter of 2016 in several countries, namely Malaysia,

Indonesia, Turkey, Singapore and Pakistan. In these countries, issuance was up 22% from the

37.3

19 9.3 8.1 5.9 5.1 2.9 1.7 1.6 1.4 1.3 1.2 1 0.6 0.4 0.3 3.1

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40