9

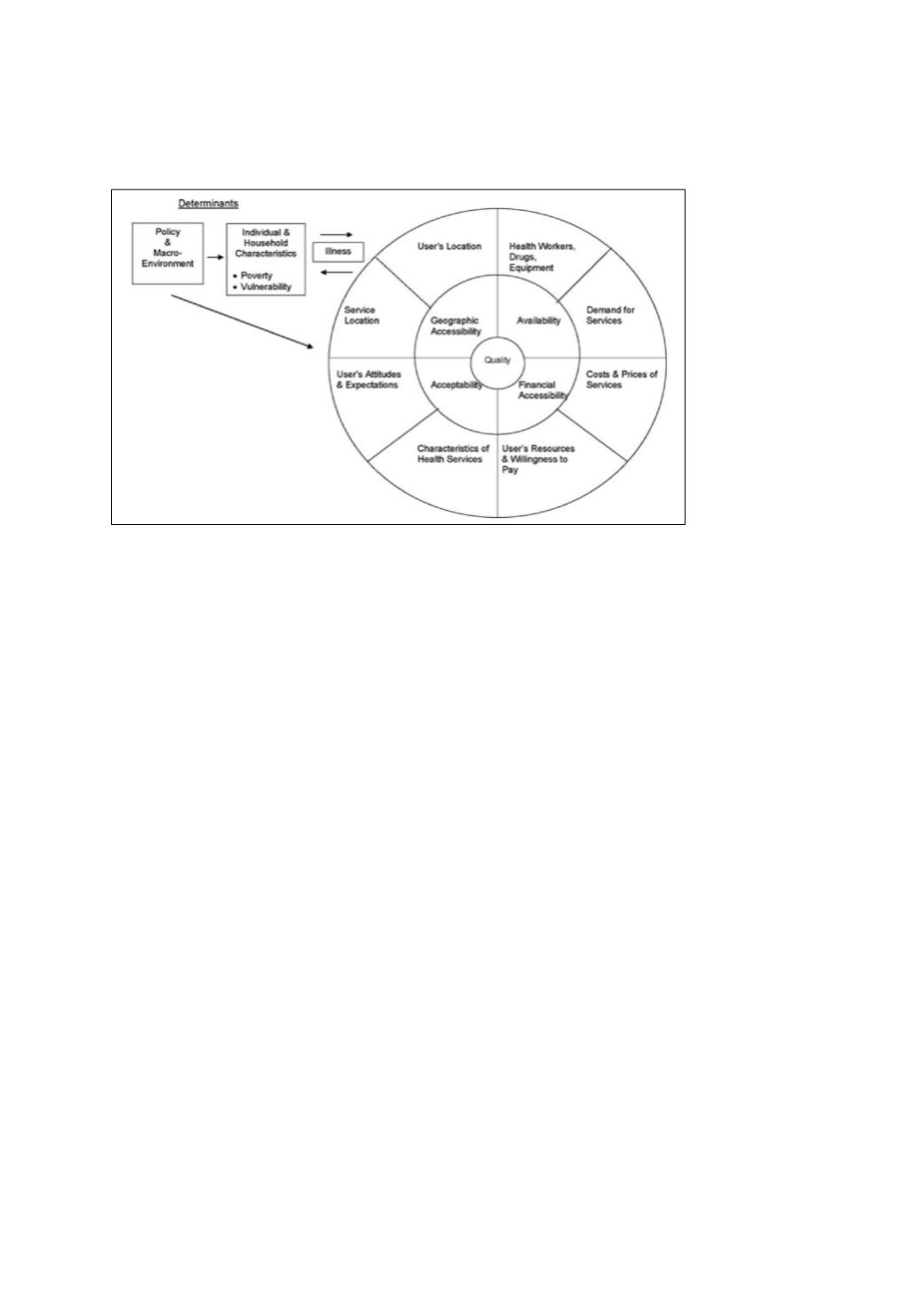

Figure 3: Conceptual framework for assessing access to health services

Source: Peters et al. (2008)

The conceptual framework shows that there are structural and population determinants which

influence characteristics of healthcare provision. The structural determinants are the macro

environment such as policy and strategy, financial crisis, inflation, etc. in relation to health. This is

evident in case of poverty; developing countries have 90 per cent of the global burden of disease but

account for only 12 per cent spending on health (cf. Hart’s inverse care law (Gottret & Schieber, 2006,

p. 3; Peters et al., 2008)). It is also crucial that health services are of good quality to be accepted. This

generally refers to the technical ability to affect people’s health, such as competence of the providers

(informed and effective health staff), facility infrastructure (e.g. hospitals), and materials (medicine,

instruments, etc) needed to ensure provision of quality services. The population determinants relate

to various sociodemographic determinates, various social groups and related household

characteristics.

While the Peter et al.’s access to health framework has been very popular so far, it lacks some social

and behavioural aspects (Culyer & Wagstaff, 1993; Culyer, 2001; Jacobs, Ir, Bigdeli, Annear, & Van

Damme, 2012). For example, the framework does not consider providers’ behaviour and interactions,

such as the lack of sense of entitlement often experienced by the poor, the lack of task shifting (“a

process of delegation whereby tasks are moved, where appropriate, to less-specialized health

workers”), responsiveness of the providers (i.e. late referral), means of transport, dualism and

absenteeism (by the service providers) and lack of awareness (Ahmed, Petzold, Kabir, & Tomson,

2006; Baine et al., 2018; Bigdeli & Annear, 2009; Fulton et al., 2911; Jacobs et al., 2012; Kiwanuka et

al., 2008; WHO, 2011). Further to this, access to healthcare is complex, underlying the very fact that

people can be treated unjustly even if they are treated equally. For example, a set of healthcare can be

available to a community, however it may not include a specific service that can be very important for

a specific group within that community, such as the elderly.

Therefore access to healthcare can be defined as “the ability to ensure a set of healthcare services, at a

specified level of quality, subject to personal convenience and cost, based on specified amount of

information” (Oliver &Mossialos, 2004, p. 656). This suggests two principles: horizontal or formal, and

vertical or proportional equity. The first one states that all people with equal/similar needs should be

treated the same, and the latter suggests that people with greater need should be treated with more

urgency than those with lesser need (Culyer & Wagstaff, 1993; Culyer, 2001; Sutton, 2002).