7

Chapter 2: Conceptual Framework

2.1

Health and development

Health was declared a human right about six decades ago. Within two years of theWHO’s endorsement

of

highest attainable standard of health

as a

fundamental right of every human being

in 1946 (WHO,

2017), the United Nations (UN) asserted health as a human right. The declaration of UN General

Assembly in Paris on December 10, 1948 stated under article 25 (1), that, “everyone has the right to a

standard of living adequate for the health of himself and of his family” (United Nations, n.d.). This right

to health also entails that the state has the legal responsibility to ensure the realization of this right;

and to put systems in place to allocate required resources provide quality healthcare accessible when

needed, and affordable and acceptable to all (WHO, 2017). From an operational point of view, this

requires a multidisciplinary system which recognises health as part of human development and

acknowledges the relationship between various socio-demographic and economic factors on the one

hand and health on the other. Socio-economic factors can result in acute and chronic deprivation from

health-related wellbeing, causing individuals and community to be disadvantaged and marginalised.

In 2015, globally about 740 million people earned less than US dollar 1.90 per day, i.e. lived in extreme

poverty. While poverty is often defined based on income status, there is a growing body of literature

that explains poverty as a social deprivation which can range from lack of income to lack of basic needs,

physical discomfort, bad relationship with others, etc. (Mabughi & Selim, 2006). Like other social

deprivations, health and poverty are intimately related. In addition to poor people having different

health outcomes compared to rich, the unequal distribution of health outcomes contributes to further

constraints and opportunities in poor peoples’ lives. For example, poor people have limited access to

healthcare, causing them to suffer from poor health outcomes, such as malnutrition and sickness,

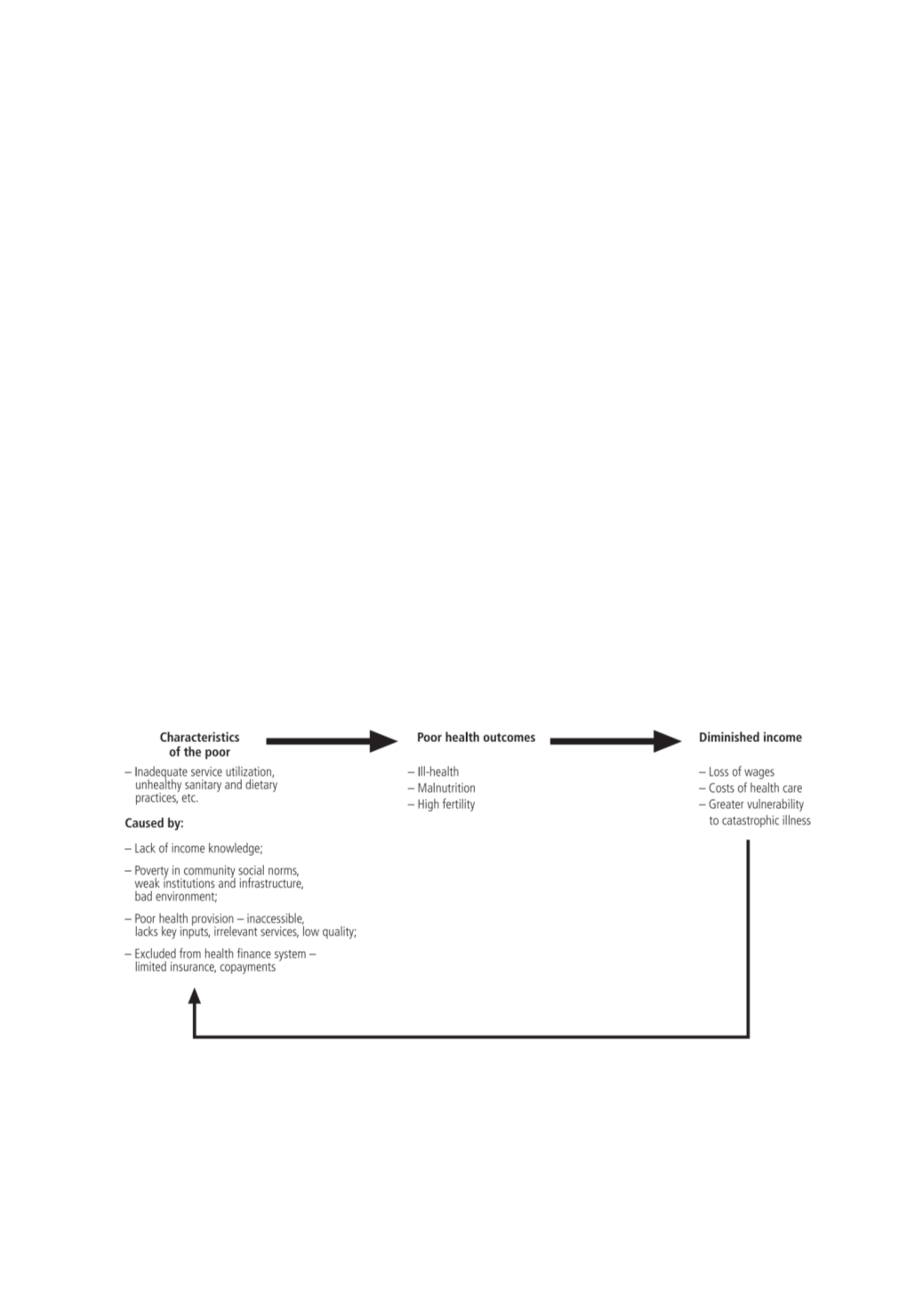

leading to reduced productivity and lower income. This can result in what is often called a

vicious cycle

,

depicted in

Wagstaff (2002)

.

Figure 2: Health and poverty cycle

Source: Wagstaff (2002)

The poverty-health cycle demonstrates two dimensions that lead to poor health outcomes for poor

people: context and access (to health). The context is related to poor living conditions, housing,

sanitation and hygiene, etc. From the health perspective, context is a risk factor for the health of the

poor. Access to health services is often restricted for the poor; either due to unavailability of services