Malnutrition in the OIC Member

Countries: A Trap for Poverty

COMCEC

(1)

(2)

(3)

Wasting Stunting Overweight

Primary education

0.95

(0.14)

1. 02

(

0

.

1 0

)

1.12

(0.14)

Secondary education

0

70***

(0.09)

0.89

(0.08)

0.85

(0.09)

Higher education

0.61***

(

0

.

1 1

)

0.91

(

0

.

1 1

)

0.98

(0.14)

Breastfed immediately

1.08

(

0

.

1 0

)

0.94

(0.06)

0.83**

(0.06)

Exclusive breastfeeding

1.05

(0.09)

0.94

(0.06)

0.90*

(0.06)

Prenatal doctor visit

0.79*

(

0

.

1 1

)

0.77***

(0.06)

0.98

(

0

.

1 1

)

Baby postnatal check after 2 months

1.03

(0.09)

1

.

1 0

*

(0.06)

1

.

2 2

***

(0.08)

Vitamin Adose within 2 months of delivery

1. 02

(0.04)

1.03

(

0

.

0 2

)

1. 01

(0.03)

Dietary diversity index

1 . 00

(

0

.

0 1

)

1 . 00

(

0

.

0 1

)

1. 00

(

0

.

0 1

)

Observations

9437

9437

9437

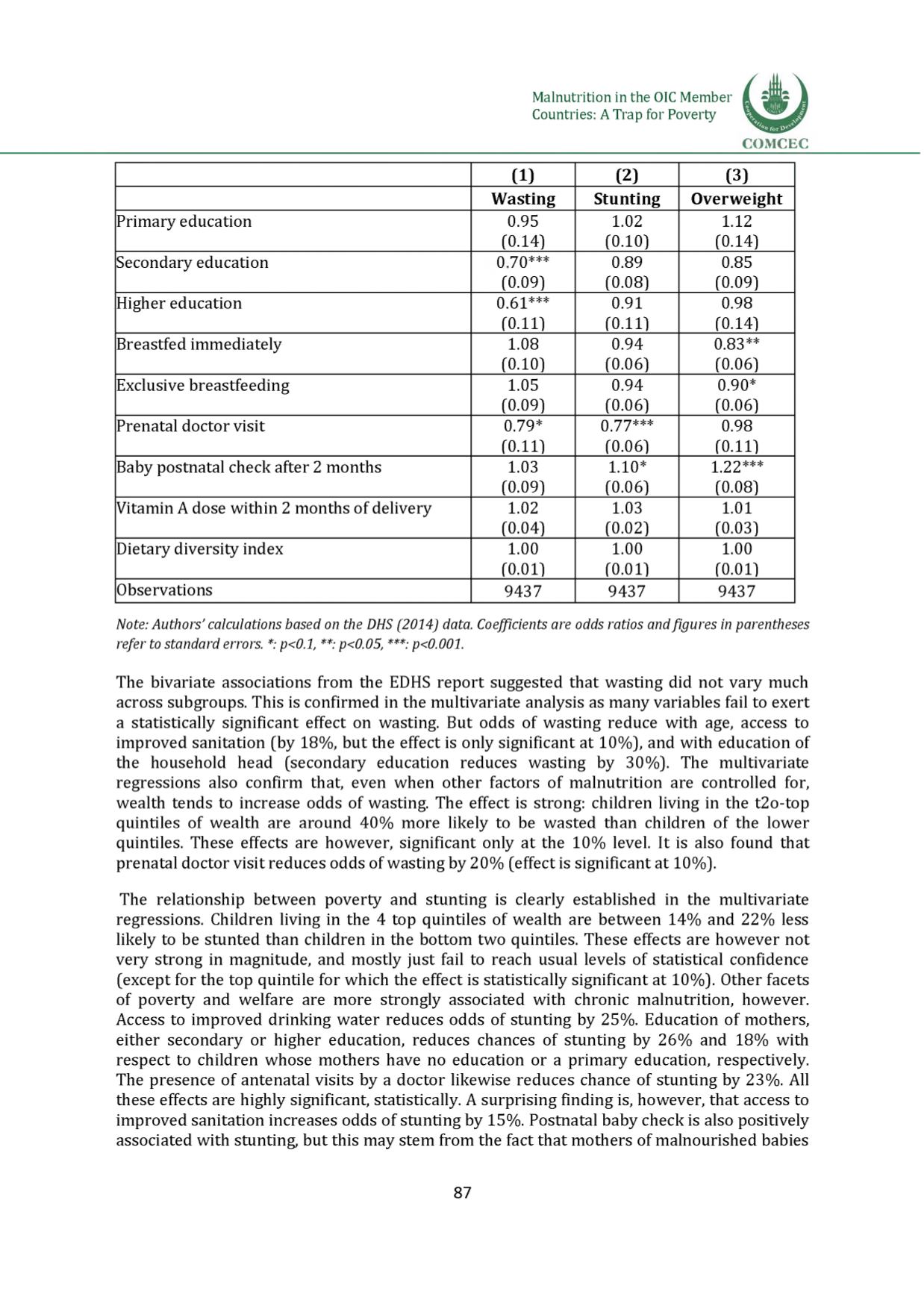

Note: Authors' calculations based on the DHS (2014) data. Coefficients are odds ratios andfigures in parentheses

refer to standard errors. *: p<0.1, **: p<0.05, ***: p<0.001.

The bivariate associations from the EDHS report suggested that wasting did not vary much

across subgroups. This is confirmed in the multivariate analysis as many variables fail to exert

a statistically significant effect on wasting. But odds of wasting reduce with age, access to

improved sanitation (by 18%, but the effect is only significant at

1 0

%), and with education of

the household head (secondary education reduces wasting by 30%). The multivariate

regressions also confirm that, even when other factors of malnutrition are controlled for,

wealth tends to increase odds of wasting. The effect is strong: children living in the t2o-top

quintiles of wealth are around 40% more likely to be wasted than children of the lower

quintiles. These effects are however, significant only at the 10% level. It is also found that

prenatal doctor visit reduces odds of wasting by

2 0

% (effect is significant at

1 0

%).

The relationship between poverty and stunting is clearly established in the multivariate

regressions. Children living in the 4 top quintiles of wealth are between 14% and 22% less

likely to be stunted than children in the bottom two quintiles. These effects are however not

very strong in magnitude, and mostly just fail to reach usual levels of statistical confidence

(except for the top quintile for which the effect is statistically significant at 10%). Other facets

of poverty and welfare are more strongly associated with chronic malnutrition, however.

Access to improved drinking water reduces odds of stunting by 25%. Education of mothers,

either secondary or higher education, reduces chances of stunting by 26% and 18% with

respect to children whose mothers have no education or a primary education, respectively.

The presence of antenatal visits by a doctor likewise reduces chance of stunting by 23%. All

these effects are highly significant, statistically. A surprising finding is, however, that access to

improved sanitation increases odds of stunting by 15%. Postnatal baby check is also positively

associated with stunting, but this may stem from the fact that mothers of malnourished babies

87