135

Quality of physical educational inputs

Governments have typically tended to pursue ‘inputs’-based educational policies in the

misguided view that improving inputs alone will improve educational quality. This is not to say

that inputs do not matter, but the critical question remains ‘which’ inputs matter most to

improve educational quality. However, research in education in recent years has questioned the

value of investments in expensive resources (such as reduced class sizes) as the relationship

between school resources and student achievement remains contested (Hanushek, 1997).

Nevertheless, there are some basic facilities without which a child’s learning experience is likely

to be compromised – the availability of a functioning toilet, safe drinking water, boundary walls

for schools, physical classroom structures, textbooks and most importantly teachers who are

qualified and have sufficient content and pedagogic knowledge to impart learning effectively to

the child.

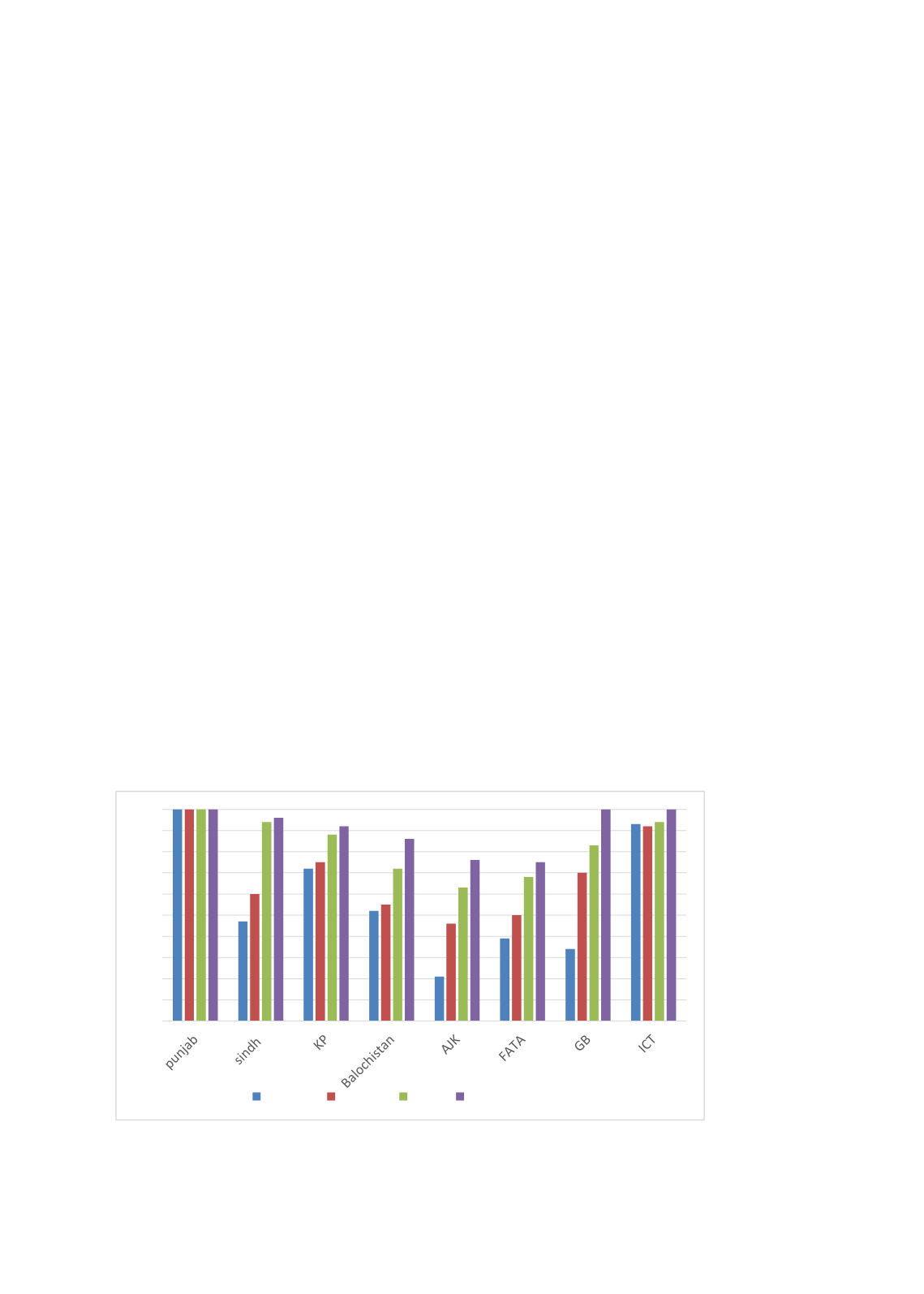

The evidence to date indicates that the quality of physical school indicators continues to remain

poor across schools in Pakistan with private schools reporting better availability of most

(though not all) facilities than government schools. There are large discrepancies across

provinces and regions with the poorer provinces such as Balochistan consistently reporting

poor educational inputs across both government and private schools. Figure 3.3.6 illustrates the

availability of drinking water by province/region and by schooling level based on PSLM data

(2015-2016). It is clear that safe drinking water is not available even based on these government

statistics across most provinces and across various education levels. ASER data from most

recent years also appears to highlight this dire state of affairs (Appendix Table A7); in

Balochistan, for example, only 14%of primary government schools reportedly had safe drinking

water and whilst private schools consistently reported better water facilities, even private

schools inmany parts of the country do not provide this basic facility to children. Similar findings

are reported for toilet facilities (Figure 3.3.7 and Appendix Table A8). The data from ASER also

consistently shows poor quality of other physical schooling facilities – with only 35% of

government primary schools reporting having playgrounds available and only 45% of private

schools indicating availability of playgrounds for children nationally.

Figure 3.3.6: Availability of Drinking Water (%), by Province/Region and Schooling Level

Source: Pakistan Education Statistics 2015-16

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

primary middle high higher secondary