National and Global Islamic Financial Architecture:

Prolems and Possible Solutions for the OIC Member Countries

189

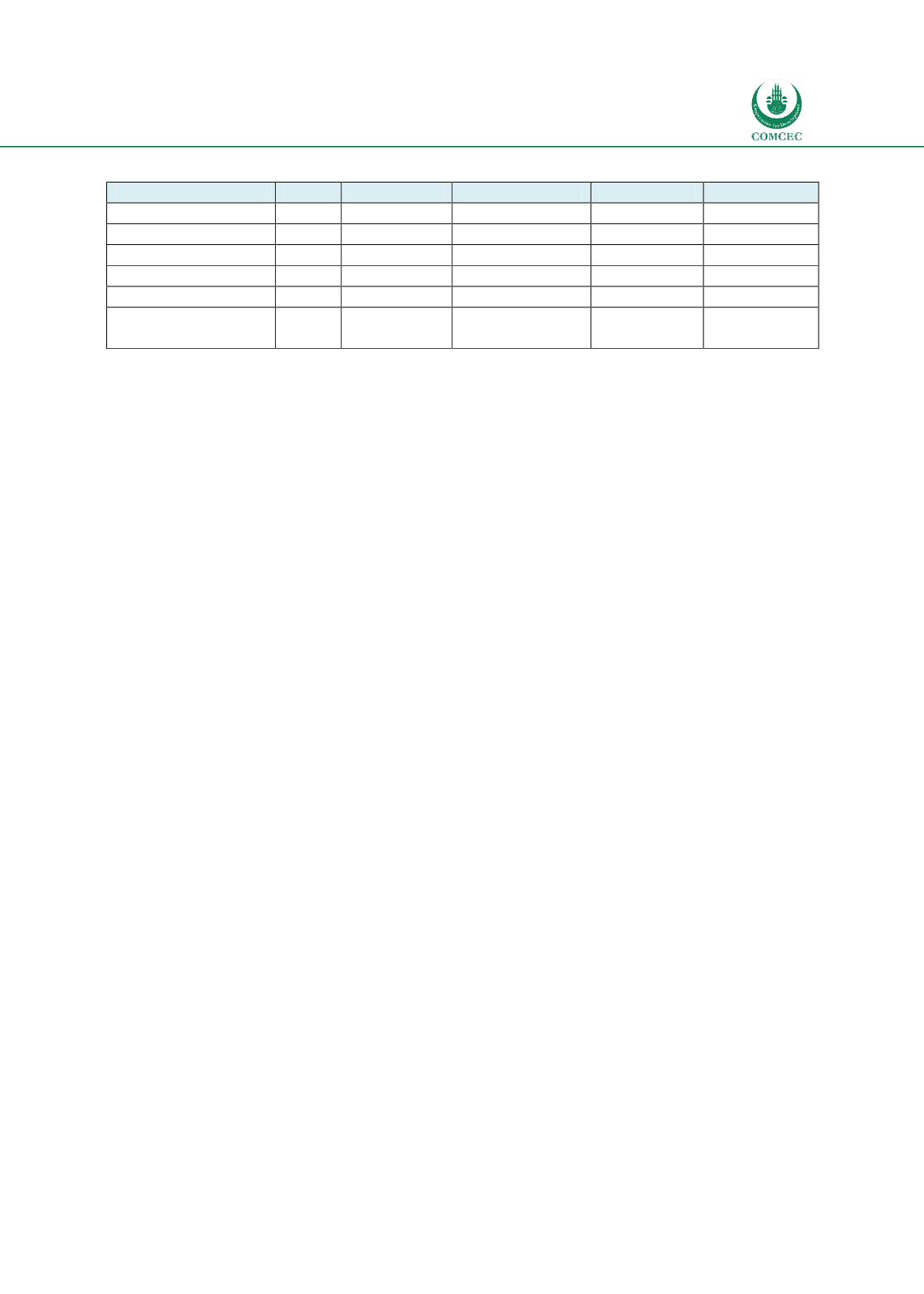

Table

5.5: Summary Status of Activities in Global Financial Centres

Activities

UK

Germany

Luxembourg

Singapore

Hong Kong

Retail Banking

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

No

Wholesale Banking

Yes

No

No

Yes

No

Takaful/Retakaful

Yes

No

No

Yes

No

Funds

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

Sukuk

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

Education/Training

Programmes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

In trying to draw lessons and conclusions from this analysis, one can look at the implications

for other global financial centres with an interest in Islamic finance, or at the implications for

OIC countries considering whether their centres may be able to challenge the existing global

centres on the back of an Islamic finance specialism. It is easier from this study to draw

conclusions about the former than the latter.

First, it is necessary to set some context. Islamic finance is less than 2% of the global financial

system. Some 80% of its assets are in the banking sector, of which 37% are in Iran, 19% in

Saudi Arabia, 9% in Malaysia and 8% in the UAE. Other GCC countries account for a further

13% (IFSB 2016). Even given the very high growth rates of Islamic finance, the amount of truly

contestable business, for international financial centres outside those countries is at present

small. It is therefore unrealistic to think that every significant financial centre in the world can

hope to achieve a viable scale in Islamic finance, even if it wanted to do so.

Several centres besides those discussed have challenged actively for the contestable market

and some have achieved an important presence in it. In Asia, although Kuala Lumpur does not

have a strong pre-existing position in conventional finance, it has had the benefits of a very

active government development strategy supported by regulatory underpinning, active

promotion, and incentives. Both Singapore and Hong Kong have, in practical terms, been in

competition with Kuala Lumpur for internationally mobile business, even leaving aside

challenges from other centres and other regions. In the Middle East, several centres have been

vying for business and in Europe there is again competition, with Dublin and Jersey having a

significant presence in parts of the market, and ambitions from other centres such as Paris.

The evidence from the centres under study is that the demand for Islamic financial products

from Muslims in developed countries operating mixed financial systems is relatively soft.

Islamic products need to be fully competitive with conventional ones for a religious preference

to operate in their favour. This in turn means that they cannot bear substantial additional

distribution costs, even if they are targeted at a dispersed minority of the population.

Achieving a viable scale is not easy as has been demonstrated in the UK, Singapore and

Germany.

It follows that the presence of a Muslim minority is of limited direct value to a centre seeking to

establish itself in Islamic finance (though it may have indirect benefits in offering a talent pool

from which to recruit, and greater knowledge of Islam among the population generally). It is

likely that established trade, financial and educational links with major Muslim-majority

countries will be much more valuable in establishing a presence than the presence of a

domestic minority.

The centres which have succeeded have built on their existing strengths and have essentially

extended (parts of) their existing offerings into the Islamic field. All have made adjustments to

their tax systems to provide effective parity of treatment between Islamic products and their