The Role of Sukuk in Islamic Capital Markets

27

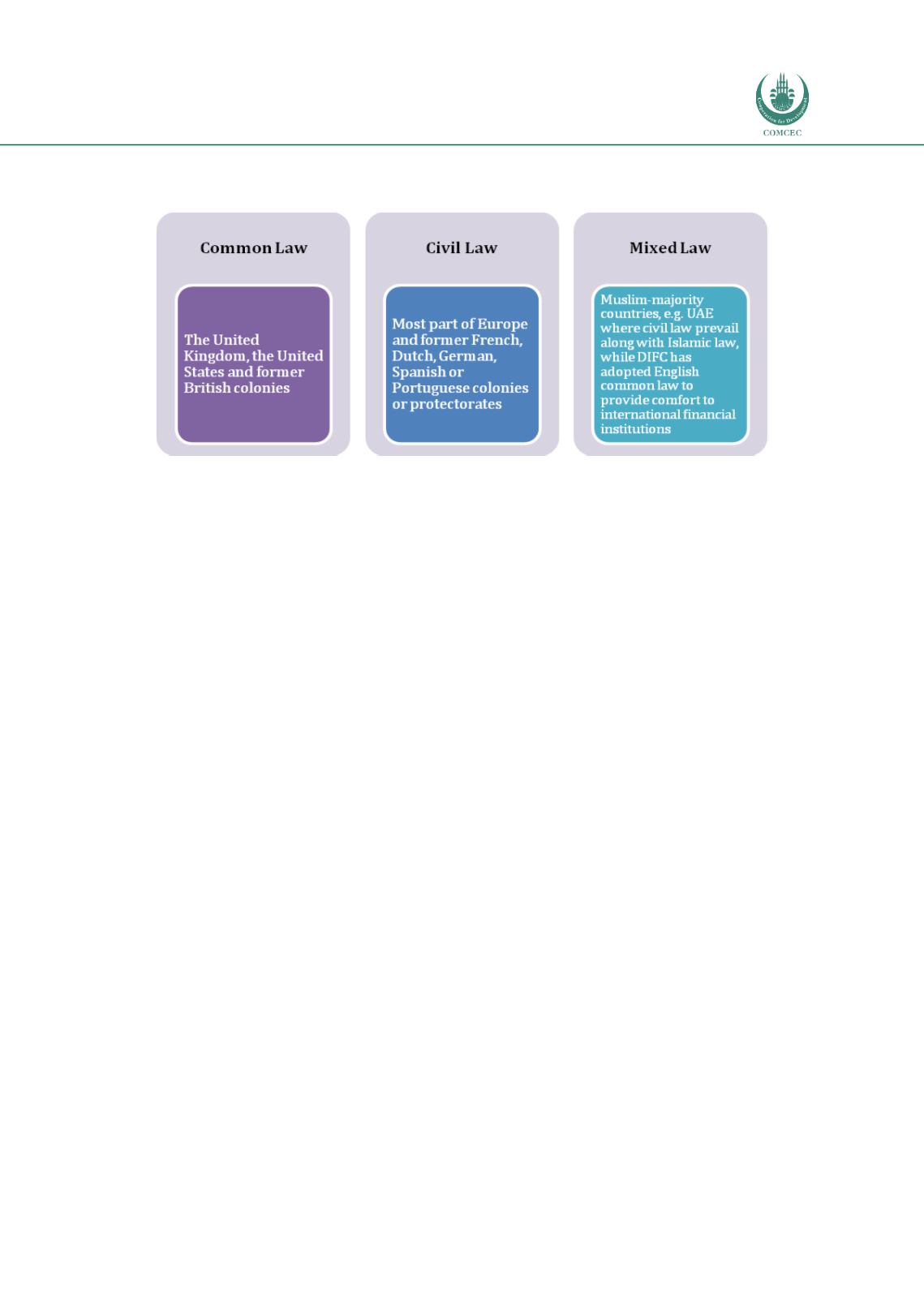

Figure 2.8: Types of Legal Systems and the Adopting Jurisdictions

Source: ISRA

Common Law vs Civil Law – Recognition of Trust Law

One of the key factors that explains the level of financial development in a country is its legal

system, and the adaptability of its laws in response to changing economic circumstances.

Arguably, legal systems based on common law are usually more flexible vis-a-vis evolving and

responding to changing conditions, as rules can be replaced based on the doctrine of

stare

decisis

(i.e. previously decided cases or precedents). Such changes in law would be more

difficult, time consuming and costly under the civil law system, which is based on statutes and

codes promulgated by the legislature and can only be amended by the legislature, introduced

by a formal procedure and considered binding on courts.

The flexibility of the common law system in the face of new cases and its adaptability to new

rules could facilitate the development of Islamic finance. A study by Grassa and Gazdar (2014)

confirms that countries with mixed legal systems based on common law and Islamic law are

favourable to the development of the Islamic finance industry. On the other hand, countries

with mixed legal systems based on civil law and Islamic law are less flexible in making changes

to their old laws, and inevitably hinder the development of Islamic finance. Another study by

Said and Grassa (2013) reveals that countries with mixed common law and Islamic law

systems have developed sukuk markets.

A key legal issue with sukuk concerns the transfer of ownership of the underlying assets to

sukuk holders. Common law jurisdictions recognize the concepts of trust and beneficial

interest, unlike civil law systems,

which only recognize ownership held by 1 party

. For

example, i

n GCC countries that apply civil and Islamic laws, the separation between legal and

beneficial ownership is not recognized. This causes a problem in transferring beneficial title of

the assets from the originator to the SPV ― without perfecting the legal transfer ― under an

asset-based sukuk structure. The implication is that with a real asset transfer on a “true sale”

basis (i.e. transfer of legal title), sukuk investors would have legal recourse over the underlying

assets (asset-backed sukuk) under a default scenario. Otherwise, the investors would only

have recourse against the obligor (asset-based sukuk).

Under asset-based sukuk structures, sukuk ownership takes place through a trust which is

widely used in common law systems. Under a trust arrangement, the SPV purchases the asset