Malnutrition in the OIC Member

Countries: A Trap for Poverty

COMCEC

(

1

)

(

2

)

(3)

Wasting Stunting

Overweight

Primary education

0.54**

0.53***

1.63

(0.13)

(

0

.

1 1

)

(0.72)

Secondary education

0.65

0.64*

1.76

(

0

.

2 0

)

(0.17)

(0.83)

Higher education

0.73

0.67

1.25

(0.37)

(0.28)

(1.34)

Breastfed immediately

0.94

1.16*

0.82

(

0

.

1 2

)

(0.09)

(

0

.

2 1

)

Exclusive breastfeeding

1.13

1.37**

1.03

(0.18)

(

0

.

2 0

)

(0.36)

Prenatal doctor visit

1. 01

1.52

0.82

(0.39)

(0.49)

(0.60)

Baby postnatal check after 2 months

0.87

1.07

0.85

(

0

.

1 2

)

(0.13)

(0.28)

Vitamin A dose within

2

months of

1.02

0.91

1.09

delivery

(0.07)

(0.06)

(0.16)

Dietary diversity index

1.05*

1

1 1

***

1. 02

(0.03)

(0.03)

(0.07)

Observations

1942

1942

1942

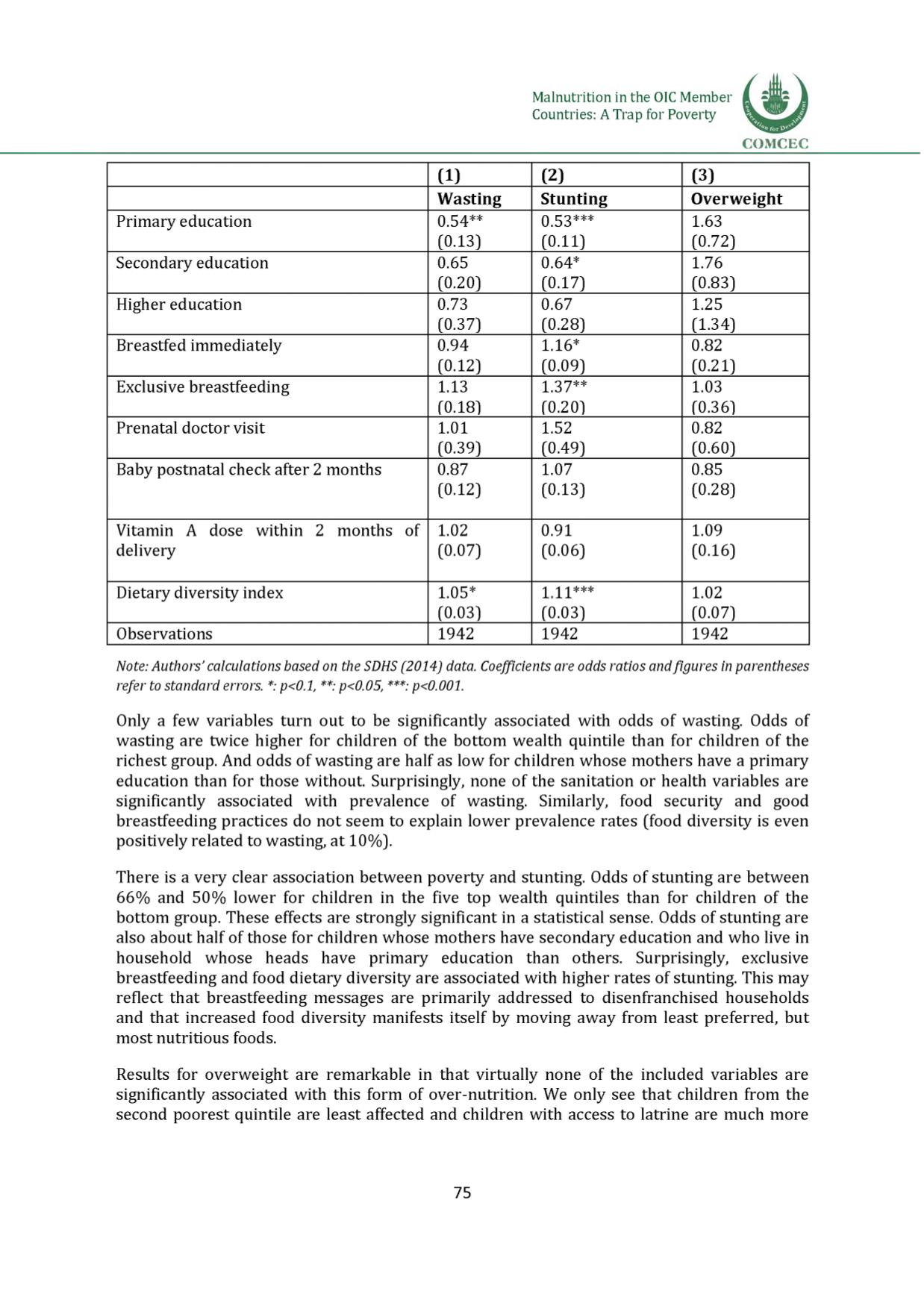

Note: Authors' calculations based on the SDHS (2014) data. Coefficients are odds ratios andfigures in parentheses

refer to standard errors. *: p<0.1, **: p<0.05, ***: p<0.001.

Only a few variables turn out to be significantly associated with odds of wasting. Odds of

wasting are twice higher for children of the bottom wealth quintile than for children of the

richest group. And odds of wasting are half as low for children whose mothers have a primary

education than for those without. Surprisingly, none of the sanitation or health variables are

significantly associated with prevalence of wasting. Similarly, food security and good

breastfeeding practices do not seem to explain lower prevalence rates (food diversity is even

positively related to wasting, at

1 0

%).

There is a very clear association between poverty and stunting. Odds of stunting are between

6 6

% and 50% lower for children in the five top wealth quintiles than for children of the

bottom group. These effects are strongly significant in a statistical sense. Odds of stunting are

also about half of those for children whose mothers have secondary education and who live in

household whose heads have primary education than others. Surprisingly, exclusive

breastfeeding and food dietary diversity are associated with higher rates of stunting. This may

reflect that breastfeeding messages are primarily addressed to disenfranchised households

and that increased food diversity manifests itself by moving away from least preferred, but

most nutritious foods.

Results for overweight are remarkable in that virtually none of the included variables are

significantly associated with this form of over-nutrition. We only see that children from the

second poorest quintile are least affected and children with access to latrine are much more

75