Malnutrition in the OIC Member

Countries: A Trap for Poverty

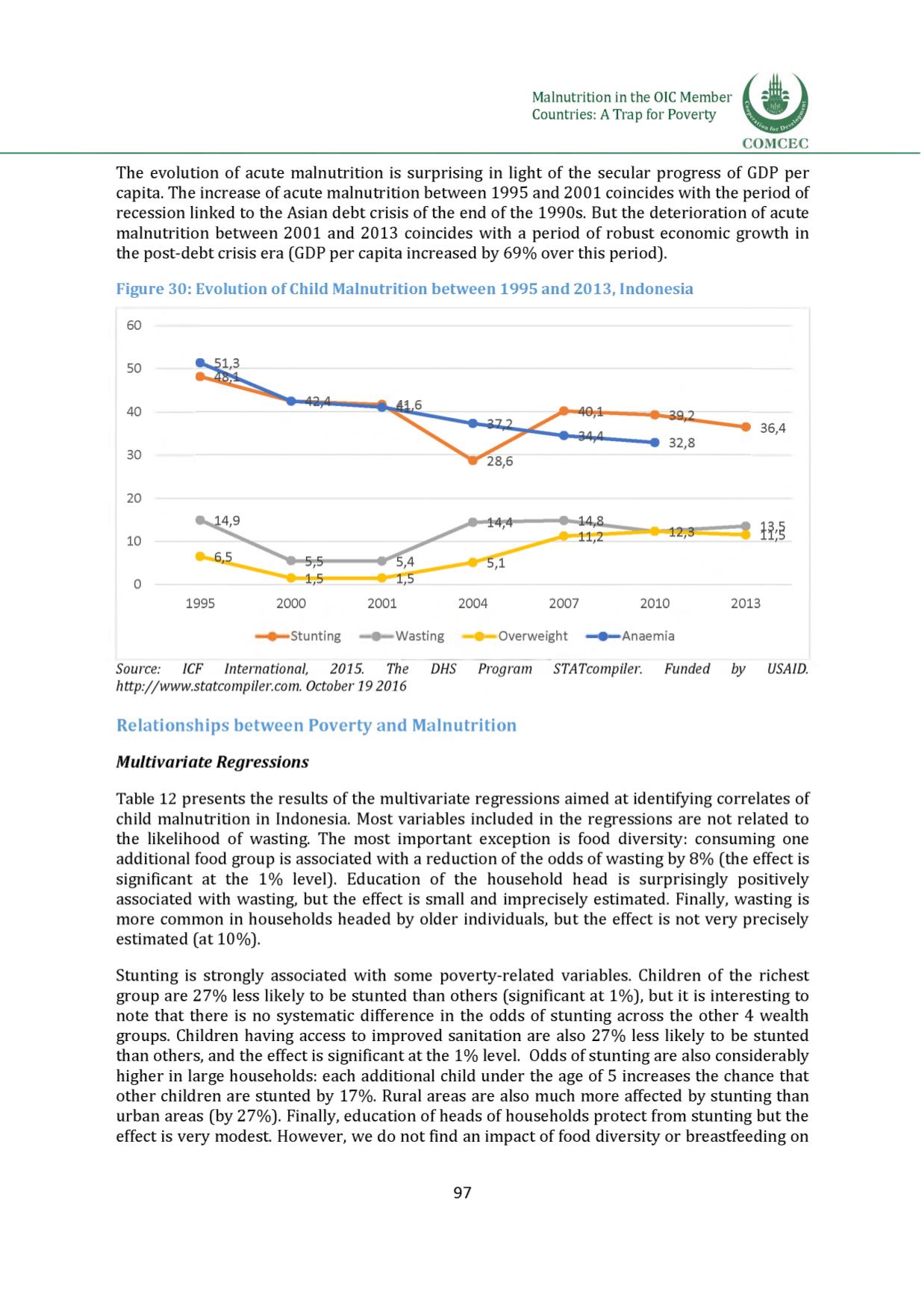

The evolution of acute malnutrition is surprising in light of the secular progress of GDP per

capita. The increase of acute malnutrition between 1995 and 2001 coincides with the period of

recession linked to the Asian debt crisis of the end of the 1990s. But the deterioration of acute

malnutrition between 2001 and 2013 coincides with a period of robust economic growth in

the post-debt crisis era (GDP per capita increased by 69% over this period).

Figure 30: Evolution of Child Malnutrition between 1995 and 2013, Indonesia

60

50

40

30

20

36,4

Stunting

9

Wasting

< Overweight

< Anaemia

Source:

ICF International,

2015.

The

DHS

Program

STATcompiler.

Funded by

USAID.

http://www.statcompiler.com.October 19 2016

Relationships between Poverty and Malnutrition

Multivariate Regressions

Table 12 presents the results of the multivariate regressions aimed at identifying correlates of

child malnutrition in Indonesia. Most variables included in the regressions are not related to

the likelihood of wasting. The most important exception is food diversity: consuming one

additional food group is associated with a reduction of the odds of wasting by

8

% (the effect is

significant at the

1

% level). Education of the household head is surprisingly positively

associated with wasting, but the effect is small and imprecisely estimated. Finally, wasting is

more common in households headed by older individuals, but the effect is not very precisely

estimated (at

1 0

%).

Stunting is strongly associated with some poverty-related variables. Children of the richest

group are 27% less likely to be stunted than others (significant at 1%), but it is interesting to

note that there is no systematic difference in the odds of stunting across the other 4 wealth

groups. Children having access to improved sanitation are also 27% less likely to be stunted

than others, and the effect is significant at the 1% level. Odds of stunting are also considerably

higher in large households: each additional child under the age of 5 increases the chance that

other children are stunted by 17%. Rural areas are also much more affected by stunting than

urban areas (by 27%). Finally, education of heads of households protect from stunting but the

effect is very modest. However, we do not find an impact of food diversity or breastfeeding on

97