Reducing Postharvest Losses

In the OIC Member Countries

82

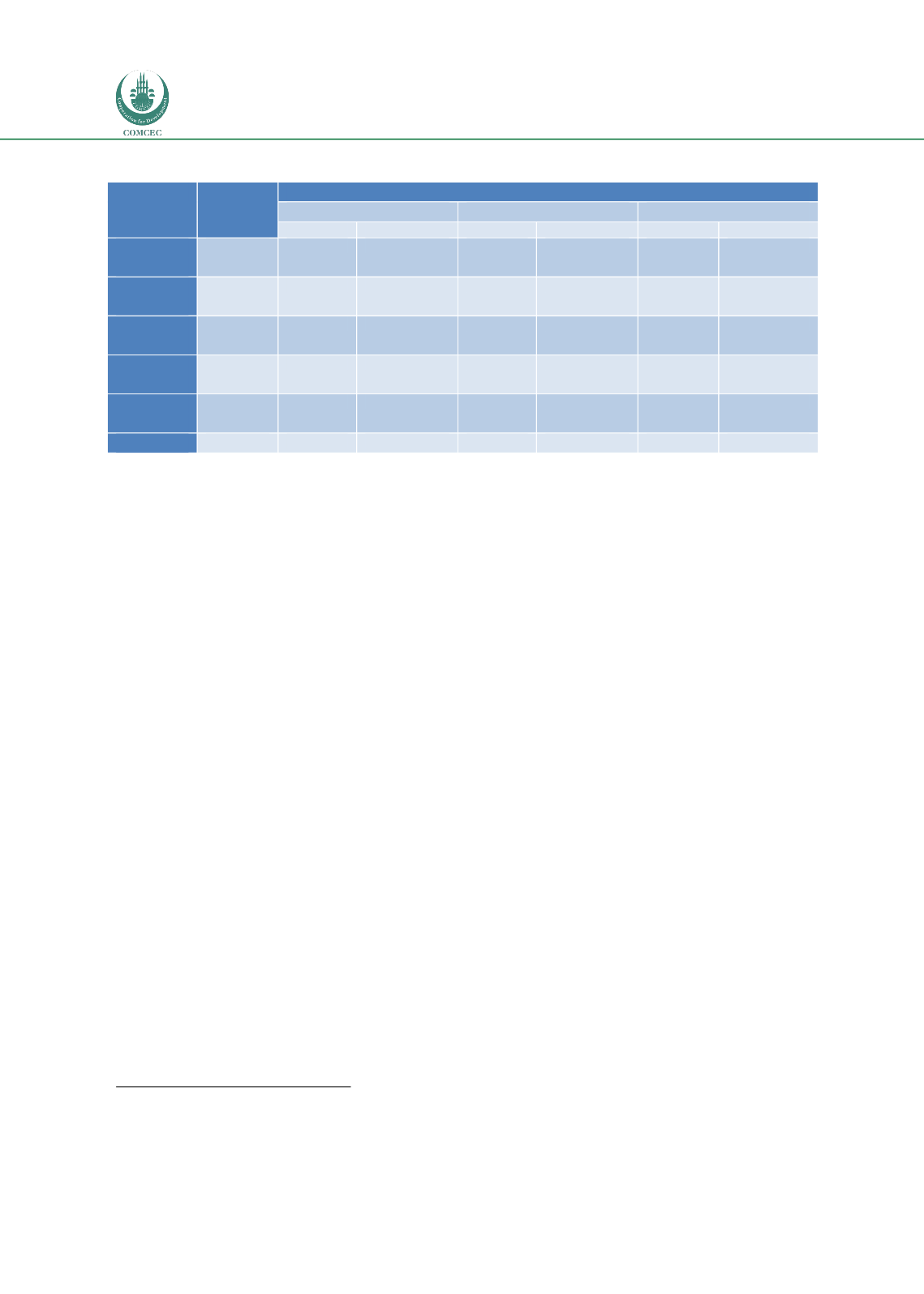

Table 43: Estimated impact of 10-30% Egyptian cereal postharvest losses

Item

2013 (t)

Hypothetical quantity and value of postharvest losses of

10%

20%

30%

t

USD

t

USD

t

USD

Wheat

produced

9,460,200

946,020

370,839,840

1,892,040

741,679,680

2,838,060

1,112,519,520

Wheat

imported

10,288,434

1,028,843

316,883,767

2,057,687

633,767,534

3,086,530

950,651,302

Maize

produced

7,956,593

795,659

210,054,055

1,591,319

420,108,110

2,386,978

630,162,166

Maize

imported

5,771,770

577,177

115,435,400

1,154, 354

230,870,800

1,731,531

346,306,200

Rice

produced

5,724,106

572,411

144,819,882

1,144,821

289,639,764

1,717,232

434,459,645

Total

39,201,103

3,920,110

1,158,032,944

7,840,221

2,316,065,888

11,760,331

3,474,098,833

Note: The above calculations use the domestic wheat procurement price of USD$392/t; and the imported wheat

price of USD308/t; (FAO, 2015); the domestic maize and rice procurement prices of USD$264/t and USD253/t

(Hamza & Beillard, 2014); and the international maize price of USD$200/t (USDA, 2016)

These rough calculations highlight the huge losses occurring if postharvest cereal grain loss

levels are even just 10%, let alone closer to 20 or 30%.

A 10% postharvest loss of all Egypt’s

domestically produced and imported wheat, maize and rice would equate to the loss of

3.9 million tons of cereal grains per annum, equivalent to USD$ 1.16 billion/ annum, or

the annual caloric requirements of at least 15 million people

(at 2,500 kcal per person per

day)

8

.

The high subsidised output prices for locally-grown wheat and maize in Egypt, might suggest it

would make more economic sense to focus postharvest loss reduction attention on the

postharvest stages of domestically produced wheat. However only between 3 and 5 million

tons of this domestically grown wheat is ever purchased at that price, with the larger

proportion ~63% of the domestically produced wheat being stored at the homesteads of the

farmers producing it.

In Egypt, farmers grow wheat as a winter crop planted in Oct/Nov, harvested in Apr/May. The

government announces its wheat procurement price prior to the planting season (currently

$357/ton (Wally, 2016)), and if farmers are dissatisfied with it this affects the wheat acreage

planted. The General Authority for Supply Commodities (GASC) sets annual targets of the

amount of locally produced wheat it wishes to purchase, but often fails to meet these targets as

the private sector traders offer farmers higher prices (Mansour & Iglesias, 2011). Farming

families

9

will keep their own stocks of cereals

10

to mill at the village mill and then produce

bread from, and some also feed livestock with cereal grains. Most farmers use sickles and

scythes to harvest their cereal crops, a few larger farmers using reaping machines (El-Lakwah,

1995). The crop is then transported from the field to the threshing place or homesteads by

camel, animal carts, donkeys, although larger-scale farmers may vehicles. The crop is placed on

the ground at the threshing place and dried using the sun and air. Most Egyptians use

8

Assuming 3,500 kcal per kg of average grain (Rosen

et al

., 2016)

9

Wheat was grown on 4.3 million farms in Egypt in 2012, 89% of farms are smaller than 1.3 ha (FAO, 2015).

10

63% of the domestically produced wheat in Egypt is kept and consumed on farm for food, seeds, feed etc., only 37% is

bought by the Government.