Reducing Postharvest Losses

In the OIC Member Countries

93

to a characteristic of cassava in Nigeria in that it is primarily a food crop compared to that

grown in Asia as a cash crop. An effect is that this maintains a higher price and demand for

fresh roots.

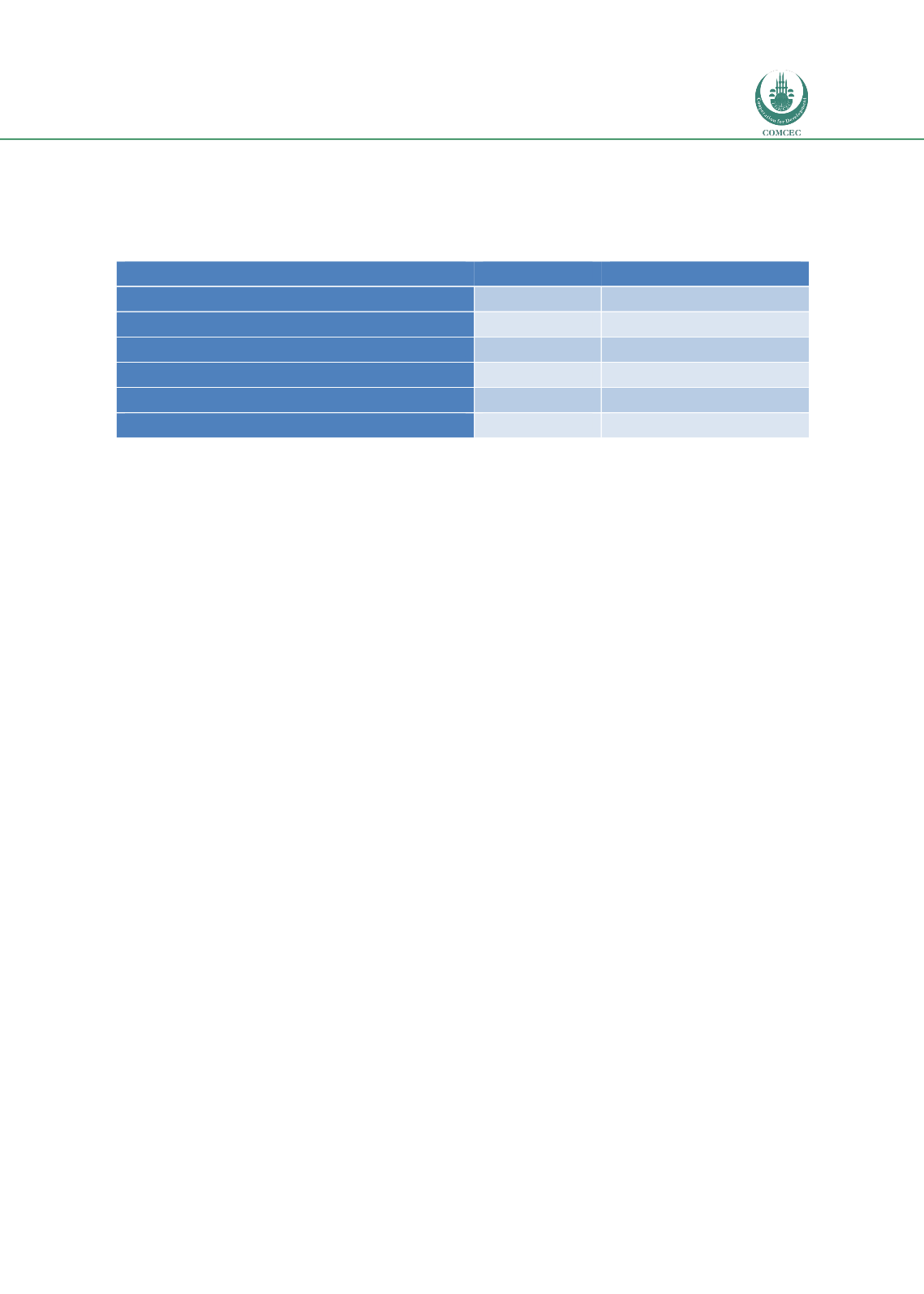

Table 45: Utilization of cassava roots for different products in South West Nigeria

Utilization

Share (%)

Fresh root use (t)

Own-consumption

20%

1,500,164

Gari

52%

3,900,426

Fufu

24%

1,800,197

Lafun

3%

240,026

Industrial, incl. dry chips and starch

1%

60,007

TOTAL

100%

7,500,820

In the light of Nigeria’s status as a cassava producer, postharvest losses of cassava and other

crops are considered to be an important issue in Nigeria. The permanent secretary, Ministry of

Agriculture and Rural Development, Mr. Sonny Echono, mentioned that postharvest losses

have been estimated to range between 5 and 20% for grains, 20% for fish and as high as 50-

60% for tubers, fruits and vegetable. While the focus of government policy is directed at

horticultural crops the Nigerian government in partnership with the private sector is working

to tackle issues of postharvest losses through the establishment of Staple Crops Processing

Zones (SCPZ), and a number of export crops handling, preservation and conditioning centres.

In the literature review, losses for cassava in Nigeria were reported as between 8% (Naziri et

al 2014) and 25% (for gari; Oguntade 2013) while the FAO gave general figures of 50% which

do not specifically refer to Nigeria. The economic cost varied from US$20 million (South West

only) and US$900 million (EUR 686 million). The differences in the value of the economic

losses reflects the differences in estimated physical losses, whether the authors are referring

to the whole of Nigeria or part and differences in value attributed to cassava.

4.2.2.

Assessment of Postharvest Physical Losses and Economic Burden

Physical losses

There are few publications that focus on the analysis of postharvest losses of cassava in

Nigeria. Of these publications, we refer to two publications being Naziri et al., 2014 and

Oguntade 2013 which estimated physical losses and the stages in the value chain where these

occur.

Naziri et al., 2014 reported that physical losses in the value chain in South West Nigeria were

estimated to be 7%. The greatest losses occurred during processing of gari and fufu at 5-8%

physical losses due to delays in processing and account for 80% of all physical losses in the

value chain. Other losses in the production of gari and fufu production for example were 1%

at the farm, 1% during transport were estimated to be 1% and negligible during trading,

transport and consumption of the finished product. For the farmers own-consumption the

roots are harvested by the farmer and usually immediately processed and there were

negligible losses in this case.

Naziri et al, 2014 proposed a range of mitigation measures to reduce losses during postharvest

processing and marketing which are listed as follows: