Forced Migration in the OIC Member Countries:

Policy Framework Adopted by Host Countries

42

migration in greater East Africa is often also protracted but sees more variation in scale and

duration, as migrants return home for periods of time when violence subsides. Many refugees

continue to rely upon these migration networks for livelihoods in times of peace, and to find

safety when violence reignites. Some countries (namely Uganda, Ethiopia, and Kenya) have

responded to protection needs through the implementation of national asylum legislation,

offering protection with UNHCR assistance. However, the lack of a regional or international

commitment to find durable solutions for refugees has left countries increasingly unwilling to

host refugees ad infinitum.

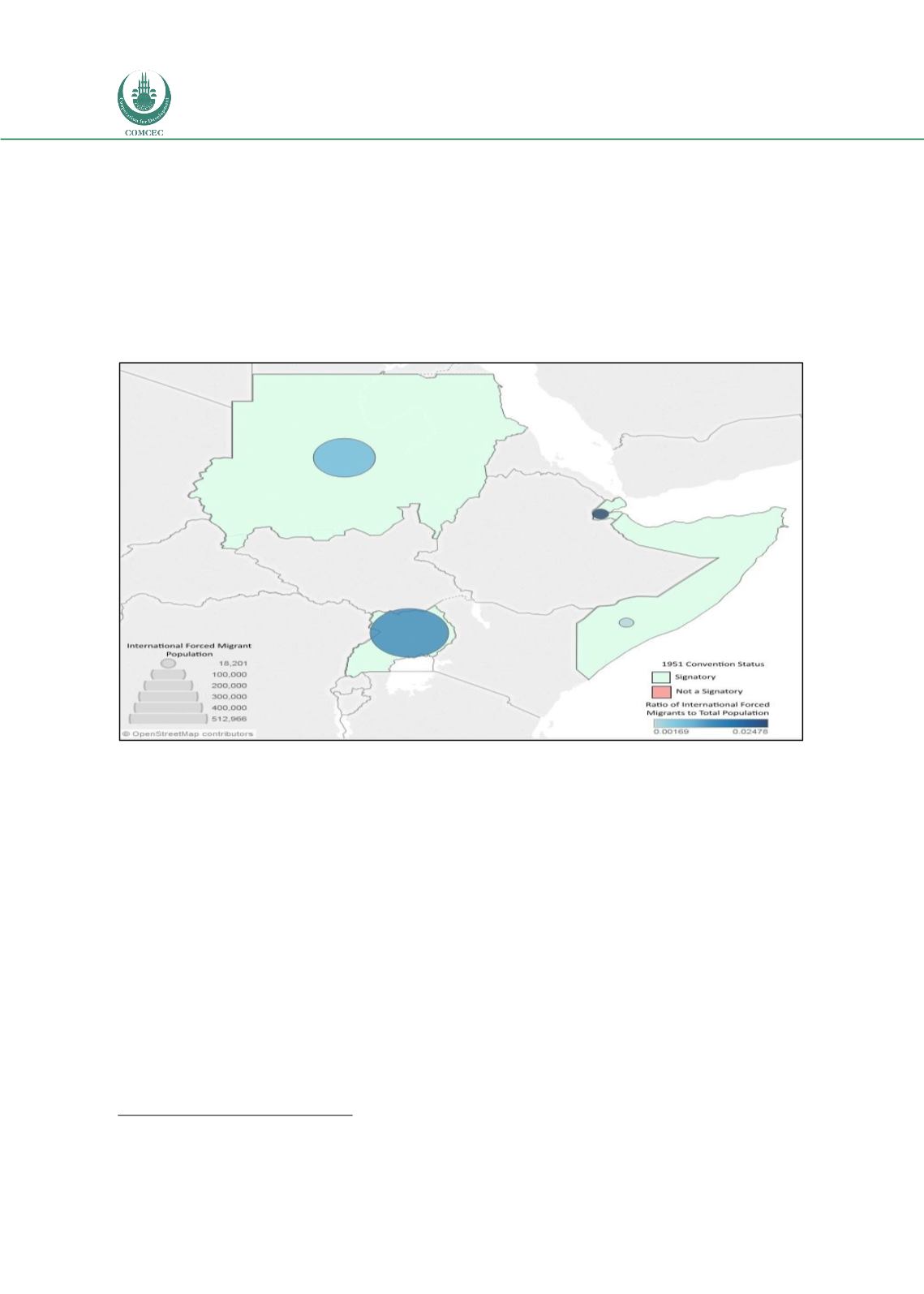

Figure 6: Forced migrant populations in OIC countries in East Africa

Source: UNHCR, “Population Statistics”

Note: The international forced migrant population is calculated to be the number of refugees, people in refugee-like situations,

and asylum seekers residing in a country.

2.5.1.

Migration dynamics in East Africa

Migration in East Africa is driven by a broad mix of chronic factors, including intermittent but

long-lasting conflicts, political persecution, drought, endemic poverty, and a young population

left with weak economic prospects. Some conflicts and drivers have become particularly

protracted, creating long-standing refugee situations, while others represent more short-term

movements. While most refugees remain in camps in the region, limited livelihood

opportunities compel some populations, such as Eritreans in particular, to move further afield

towards North Africa, the Middle East, or even Europe.

The Horn of Africa: Protracted drivers of forced migration with little chance for return

Two of the most prominent refugee situations in the Horn of Africa, those of Somalis and

Eritreans, are notable for their particularly protracted natures and the inability of migrants to

use coping mechanisms seen in other regions, such as circular migration.

134

In both instances,

134

In one survey by the Danish Refugee Council and the Norwegian Refugee Council, only 6 percent of Somali refugees

interviewed in Kenyan and Ethiopian camps said that they had been back to Somalia since fleeing the country. Danish