Governance of Transport Corridors in OIC Member States:

Challenges, Cases and Policy Lessons

54

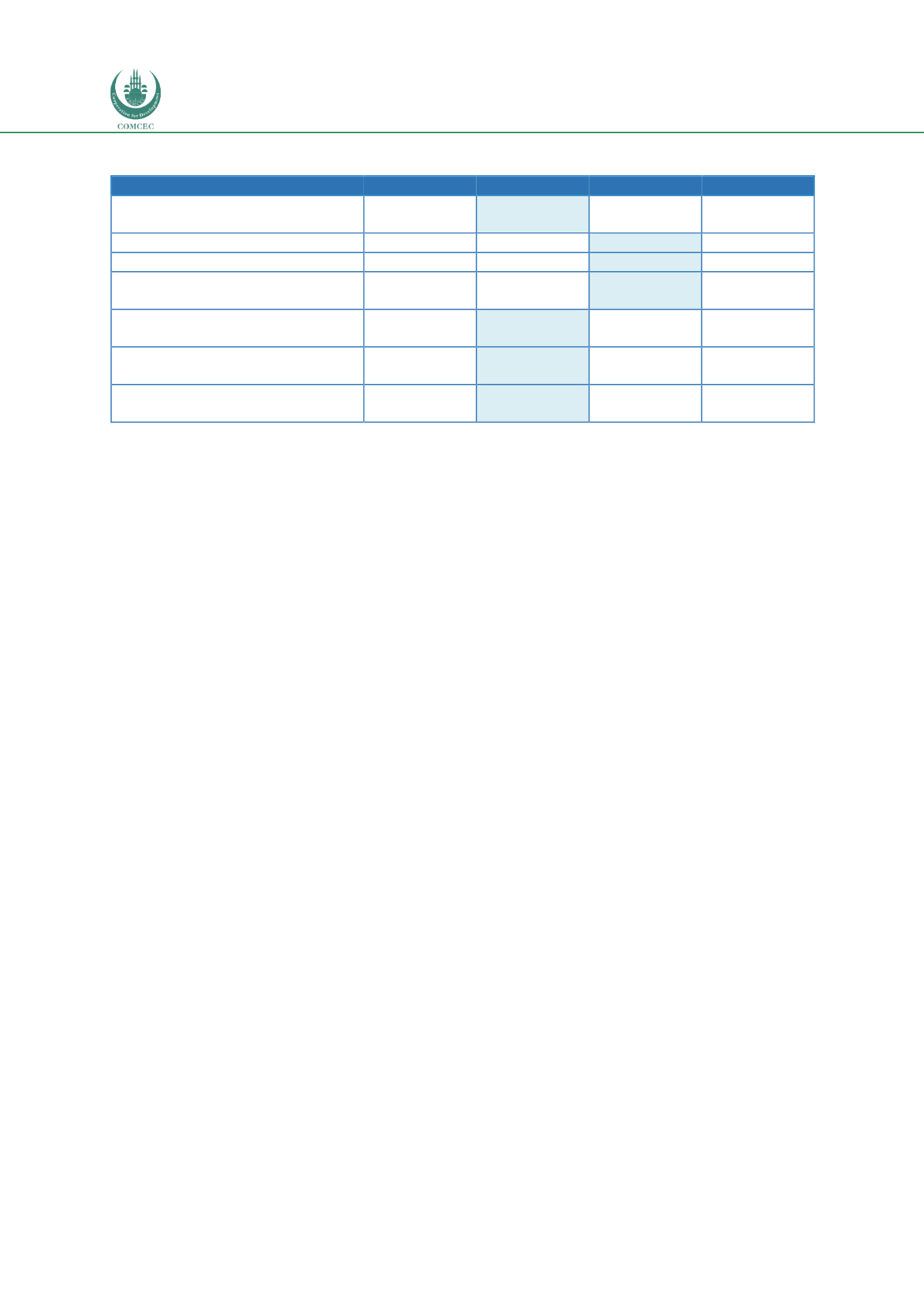

Table 3.9 SEETO corridor governance levels

Governance domains

Information

Coordination Cooperation

Integration

Corridor objectives and political

support

Legal framework

Institutional framework

Infrastructure: financing, planning

and programming

Corridor performance monitoring

and dissemination

Corridor promotion and

stakeholder consultation

Capacity building: technical

assistance and studies

Source: consortium.

3.2.10

Conclusion

Some lessons can be learned by the OIC member countries from SEETO. The first relates to how

countries that share a history of internal disputes can successfully collaborate at a regional level. The

common transport (corridor) agenda, which literally connects countries, provides a strong basis for

collaboration.

In addition, certain governance domains are developed at certain points in time in the development of

the corridor. After the signing of a MoU in 2004, SEETO developed slowly but steadily. Once the

secretariat was established in Serbia, the main topics for transport policy integration focussed on data

harmonisation and developing a methodology for priority investments. Once hard infrastructure

projects were on its way and detailed data could be collected on the performance of route segments or

transport modes, the way was paved to gain more support for demanding, but equally rewarding soft

infrastructure measures. After the development of a SEETO Priority Rating system and the release of

the third version of SEETO’s information system in 2012, SEETIS 3, the focus of the SEETO yearly

published Multi-Annual Plans slowly turned towards addressing non-physical barriers, such as

developing intelligent transport systems, harmonizing border crossing procedures, implementing

road safety guidelines or a common infrastructure maintenance plan. The trend towards

harmonisation standards and procedures was propelled forward in 2017 after the member states

signed the Transport Community Treaty; the successor of the MoU from2004. The new treaty requires

more political commitment by the members and a redesign of the corridor secretariat, giving it more

tasks and responsibilities.

The process of SEETO’s development suggests that in the cooperation stage, it is beneficial to focus on

systems of data collection to track corridor performance. However, the secretariat requires enough

capacity in the first place to achieve these goals. Then, the whole corridor is elevated to the next level

by signing a treaty that requires more commitment on all governance domains.

Another key lesson to be drawn from SEETO is that support by an international organisation

significantly speeds up the integration process. The knowledge, resources and the role of independent

mediator are valuable for consensus building. SEETO cannot be seen separate from the EU. The EU

initiated its establishment, takes part in every governance institution, provides technical assistance

and the recently established Connectivity Agenda is crucial for the future development of the network.

By 2013, the SEETO network was formally acknowledged by the EU as the indicative extension of its