Preferential Trade Agreements and Trade Liberalization Efforts in the OIC Member States

With Special Emphasis on the TPS-OIC

165

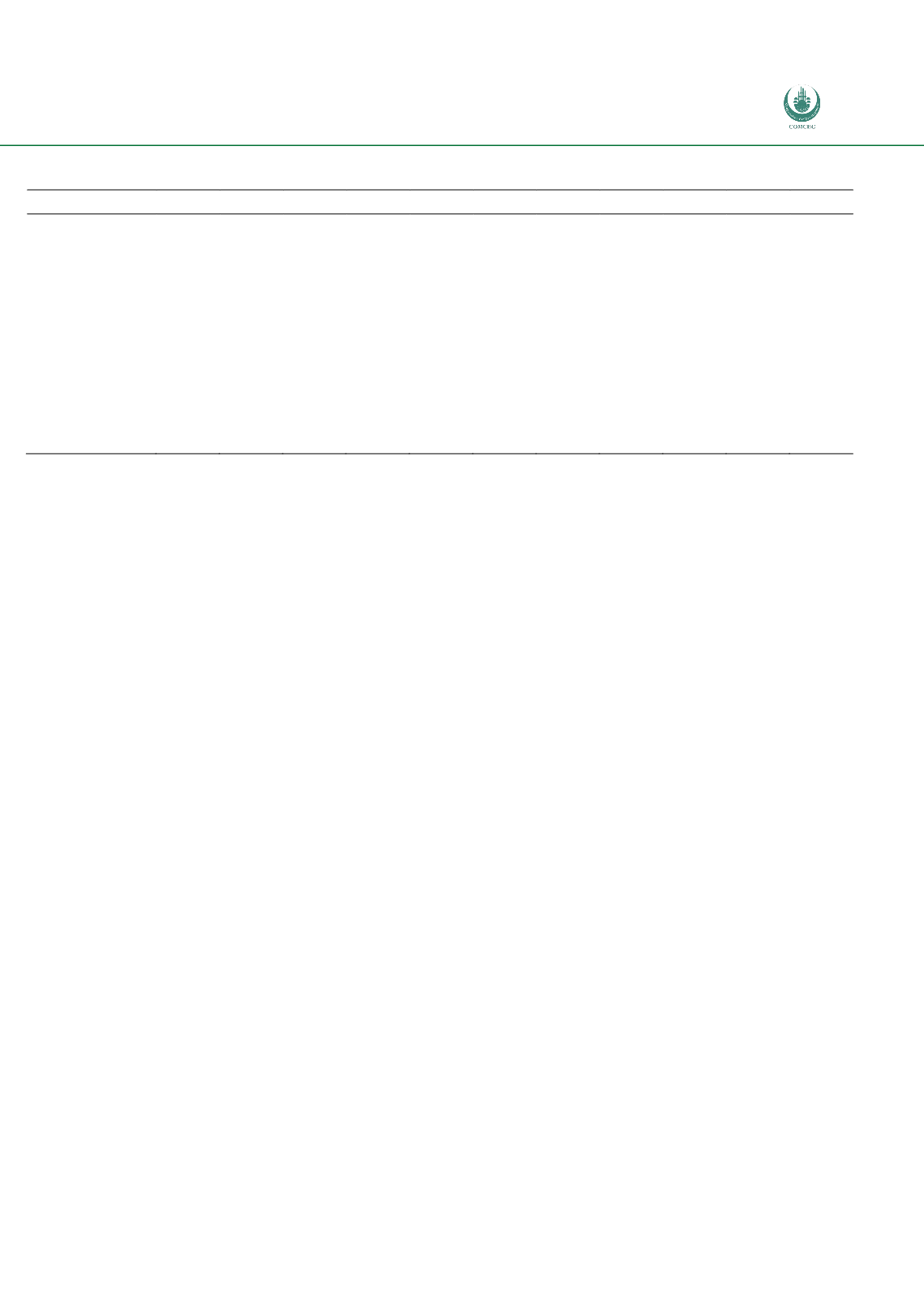

Table 34: FK Index of Export Similarity Between the TPS and the World (non-oil exports)

Reporter

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

Bahrain

0.22

0.20

0.19

0.17

0.16

0.27

0.28

0.23

0.25

Bangladesh

0.14

0.19

0.24

0.31

0.37

Jordan

0.44

0.44

0.48

0.47

0.50

0.48

0.48

0.53

0.54

0.52

0.55

Malaysia

0.34

0.34

0.36

0.36

0.36

0.40

0.38

0.38

0.40

0.41

0.40

Oman

0.19

0.38

0.37

0.41

0.41

0.44

0.50

0.49

0.46

0.53

Pakistan

0.61

0.58

0.56

0.53

0.53

0.58

0.57

0.54

0.54

0.47

0.48

Qatar

0.20

0.27

0.27

0.17

0.29

0.44

0.40

Saudi Arabia

0.62

0.73

0.72

0.69

Turkey

0.38

0.39

0.37

0.36

0.37

0.36

0.44

0.41

0.44

0.45

0.45

UAE

0.24

0.24

0.34

Source: TradeSift calculations using HS 6-digit data from Comtrade via WITS

In table 35 we present the top 20 TPS-OIC imported products from the world and the intra TPS-OIC

imports in these products. These top 20 imported products represent 26% of total TPS-OIC imports

but represent almost 41% of the intra TPS-OIC imports. Oil is again the product that seems to create

the discrepancy. Whilst in total imports this product represents almost 6% of total imports, it jumps

to more than 26% when intra TPS-OIC imports are considered. The other key products that appear to

be sourced internally are Gold, Jewellery, and Bars and rods of iron-ore / steel. The share of

electronic products and components, vehicles, and aircraft parts coming from the world as opposed

to from intra-bloc trade is significantly higher. This is not surprising as these are all products where

it is likely that the comparative advantage lies outside of the TPS-OIC region. But it also suggests, that

to the extent that the Contracting Countries of TPS-OIC also produce the goods within the bloc, and to

the extent that they offer each other preferential access in those goods there may be some scope for

trade diversion. One way of exploring this is to consider the degree of similarity in the structure of

what the Contracting Countries of TPS-OIC import from the world, and the structure of what they

export to the world. Once again this can be done with the FK index. If we do this we see that the index

is just over 0.3, suggesting a 30% degree of overlap when calculated at the 6-digit level and excluding

oil and gas. This suggests that there may be some scope for trade diversion.

Another way of addressing this issue is to also consider the degree of competitiveness of the

Contracting Countries of TPS-OIC in the products that they import from the world. If we take the top

50 products imported by the Contracting Countries of TPS-OIC these represent 37.6% of their

imports. These same products account for over 60% of the OIC countries exports, and this is because

of the dominance of oil and gas products. If we exclude oil and gas then these products account for

29.9% of imports and just under 12% of exports. Out of the 50 imported products the Contracting

Countries of TPS-OIC have a positive revealed comparative advantage in 16 of these products, of

which 13 are non-oil or gas. These 13 products account for 8.22% of total TPS-OIC exports. Once

again this suggests that there could be scope for some trade diversion, but it is unlikely to be very

substantial.