3

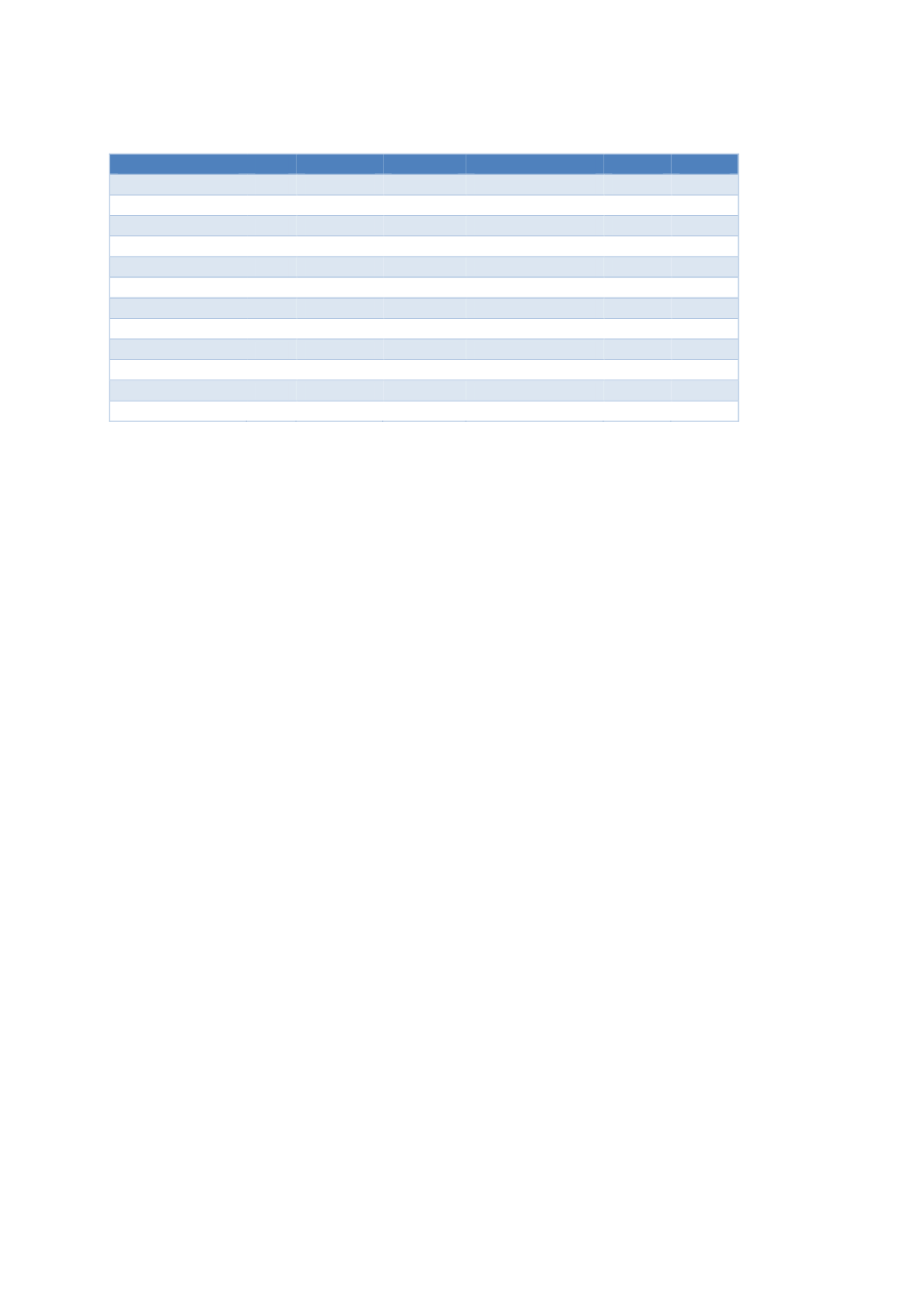

Table 1.1. World exports by provenance and destination, 2000-2011

From / To

Year World

Dev. Eco* Dev. Eco and Asia Asia

CIS

World

2000

6,337,728

4,374,811 4,865,867

413,656 77,400

2008

15,944,019 9,579,224 10,907,672

811,553 516,895

2009

12,400,610 7,209,429 8,131,100

608,252 313,419

2010

15,032,972 8,403,203 8,956,589

153,677 399,709

2011

17,831,769 9,744,886 11,133,418

909,720 478,812

World

Dev. Eco

Asia

Dev. Eco and Asia 2000

556,339

283,778

30,765

2008

998,843

383,873

80,118

2009

759,418

268,557

57,392

2010

1,007,411

331,697

73,639

2011

1,106,448

364,474

85,517

* Developed Economies

Source: 2011 International Trade Statistics Yearbook, UN Comtrade Yearbook, 2011

1.2.

Internationalisation and SMEs

Internationalisation among small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) is a topic of considerable

relevance, due mainly to the growth effects of cross-border venturing, and the demonstrated capacity

of SMEs to drive economic development at national, regional and global levels (OECD, 2009). Over

the last few decades, many SMEs explored international venturing as a requirement of business

success (Knowles et al., 2006; Rundh, 2007; Saixing et al., 2009). Many firms elected to operate

internationally as proactive players in the global economy (Zain and Ng, 2006; Brouthers and Nakos,

2004). The experience of internationalization by SMEs is sometimes comparable to those of large

firms.

What helps facilitate opportunities for SME internationalization are the considerable advances in

technology and the reduction of costs of international transportation and communication, the lowering

of trade barriers, the shortening of product and technology life cycles, and large multinational

enterprises both collaborating and competing against SMEs in their own domestic market (Rasmussen

et al., 2001; Etemad, 2004).

Despite these advantages, the SME share in the total value of international trade is often found to be

markedly lower than their share in gross domestic product (GDP). There is some evidence of the

barriers facing SMEs seeking to access international markets (OECD, 2008, 2013). Across countries at

different levels of development, the distribution of export is highly skewed in the business population.

This means that a few firms generally dominate a country’s share of export. These are mainly large

firms, whereas SMEs appear to be under-represented in the international economy relative to their

contribution to national and regional economies. Figure 1.1 illustrates that, in a large number of OECD

countries, SMEs have a much lower propensity to export than large firms.

In other words, it is common to observe that countries’ extensive margin of exports, i.e. the number of

firms selling abroad is driven by firms with more than 249 employees. The relationship between firm

size and export propensity holds when differentiating between micro, small and medium sized firms.

Specifically, the share of exporting small firms (10-49 employees) is larger than that of micro firms

(1-9 employees), while medium-sized firms are by far the most exporting sub group of SMEs. This

pattern suggests that SMEs as a whole display substantial differences in their propensity to export. In