Reducing Postharvest Losses

In the OIC Member Countries

23

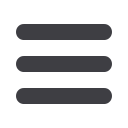

5.81

8.85

23.43

38.86

6.55

18.5

Harv

Thre

Dryi

Stor

Tran

Milli

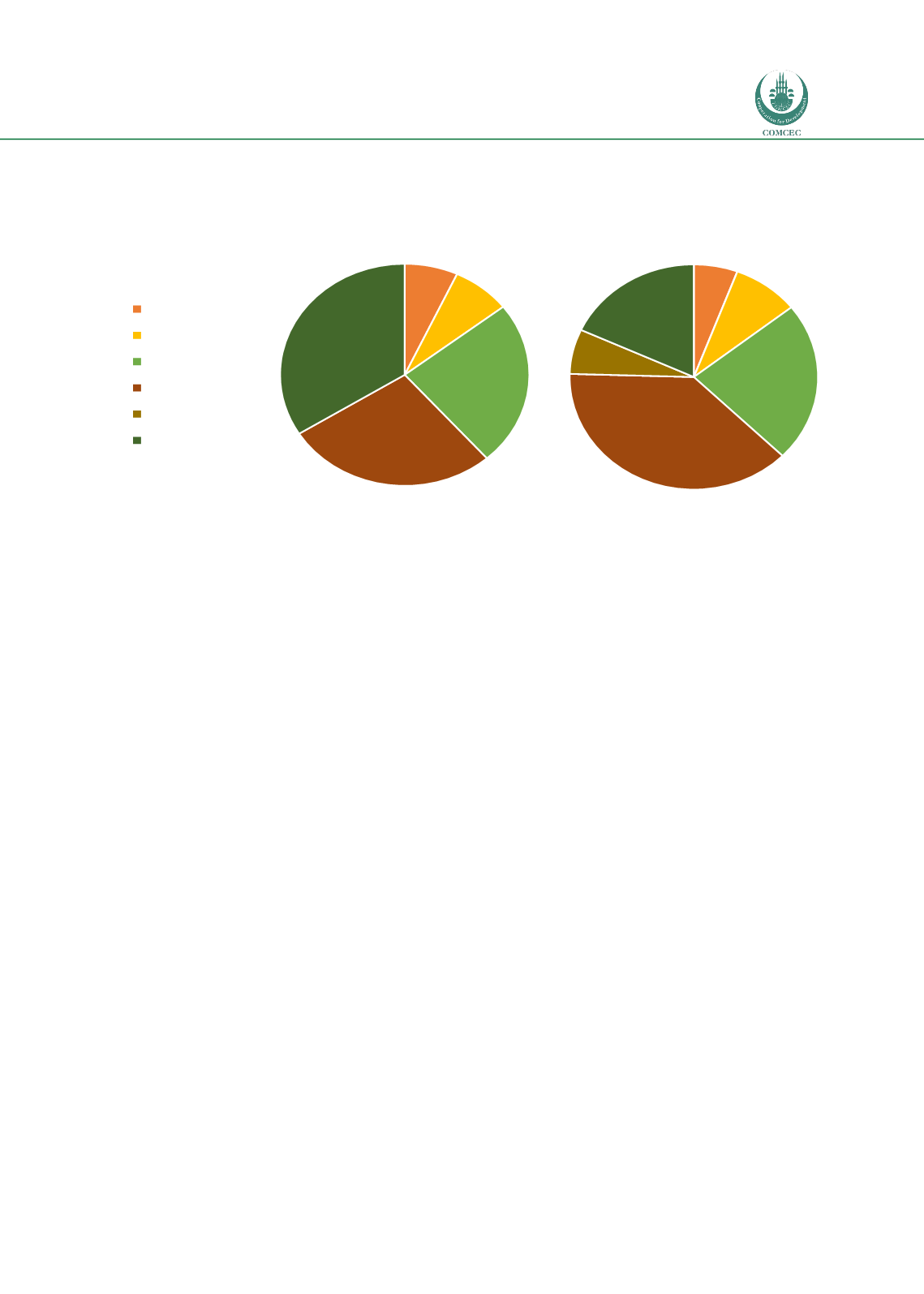

6.90

7.60

24.05

27.54

33.90

Harvesting

Threshing

Drying

Storage

Transport

Milling

Central and south-eastern Asia

Estimated % postharvest weight loss = 13%

China

Estimated % postharvest weight loss =

14.8%

Figure 6: Comparison of the proportion of rice postharvest losses occurring at different

activity stages

Sources: Calverley (1994) cited in Grolleaud (2002); IDRC (1987-1989)

Opinions differ regards whether mechanising processes would reduce the quantity of rice lost

PH, although it is recognised that mechanisation usually brings time and labour savings, but

can be financially costly to access, with insufficient skills for operating equipment PHL could

increase (Grolleaud, 2002). In Indonesia rice is still traditionally threshed using the slow and

labour intensive method of beating the rice stems with bamboo sticks which leads to high

losses (Riady

et al

., 2015). Although rice threshing machines are available, they are typically

expensive, rarely work optimally with power supply often a problem. For example, milling

losses in Indonesia reduced when milling machinery was introduced, but as the machinery

aged this gain declined (e.g. mechanised rice-milling ratio for paddy declined from 70% to

60% as machines aged) (Simatupang & Timmer, 2008). IRRI researchers’ estimates of

comparative losses in traditional and mechanised PH rice chains suggest a wide range of loss

can occur with both traditional and mechanised process.

Two comprehensive studies of paddy losses in Indonesia in 1986/7 and 1994/5 suggested

total harvest and postharvest losses were ~21%, with 15% occurring during harvesting and

threshing (Maksum, 2002 cited in Simatupang and Timmer, 2008). Earlier work in Indonesia

highlighted the links between the labour organisation system used and harvesting losses, and

the technology for threshing losses. The largest losses (18.6%) occurred with open-access

harvesting and the slapping paddy threshing system, and the lowest (5.9%) with labour-group

(or trader-harvester) harvesting and mechanical threshing (Hasanuddin

et al

., 2002). A much

earlier Indonesian study reported the harvest loss with the open-access system reaching a

massive 42.5% of total yield loss, owing to stamping-down, dropping and left-over losses, as

well as transportation losses between field and home (Utami and Ihalauw, 1973).

In Bangladesh, two studies thirty years apart compared PHL along the rice chain and between

different stakeholders. The 2010 farmer level data came from a survey of 944 marginal, small,

medium and large farmers. In contrast to the Indonesian study, these studies (as did the

Central and south-east Asian studies) found the largest rice PHL occurred by farmers are

during storage and drying. Although, in Bangladesh rice is often produced in 3 seasons each

year with PHL differing by season and location. Processors incur more rice PHL during milling

than drying or parboiling, and wholesaler and retailer rice PHL occur mainly during storage

and transport

(Table).