Reducing Postharvest Losses

In the OIC Member Countries

120

markets. Given that the seller does not get the full market value of the milk it has been

assumed that 70% of the value is retained and there is a 30% loss in value through forced

consumption of milk at the farm level.

Other causes of on-farm loss include spillage, milking practices (e.g. cleaning of udder, type of

milking utensils used), lack of cooling, and animal diseases affecting the amount and quality of

milk produced (e.g. mastitis).

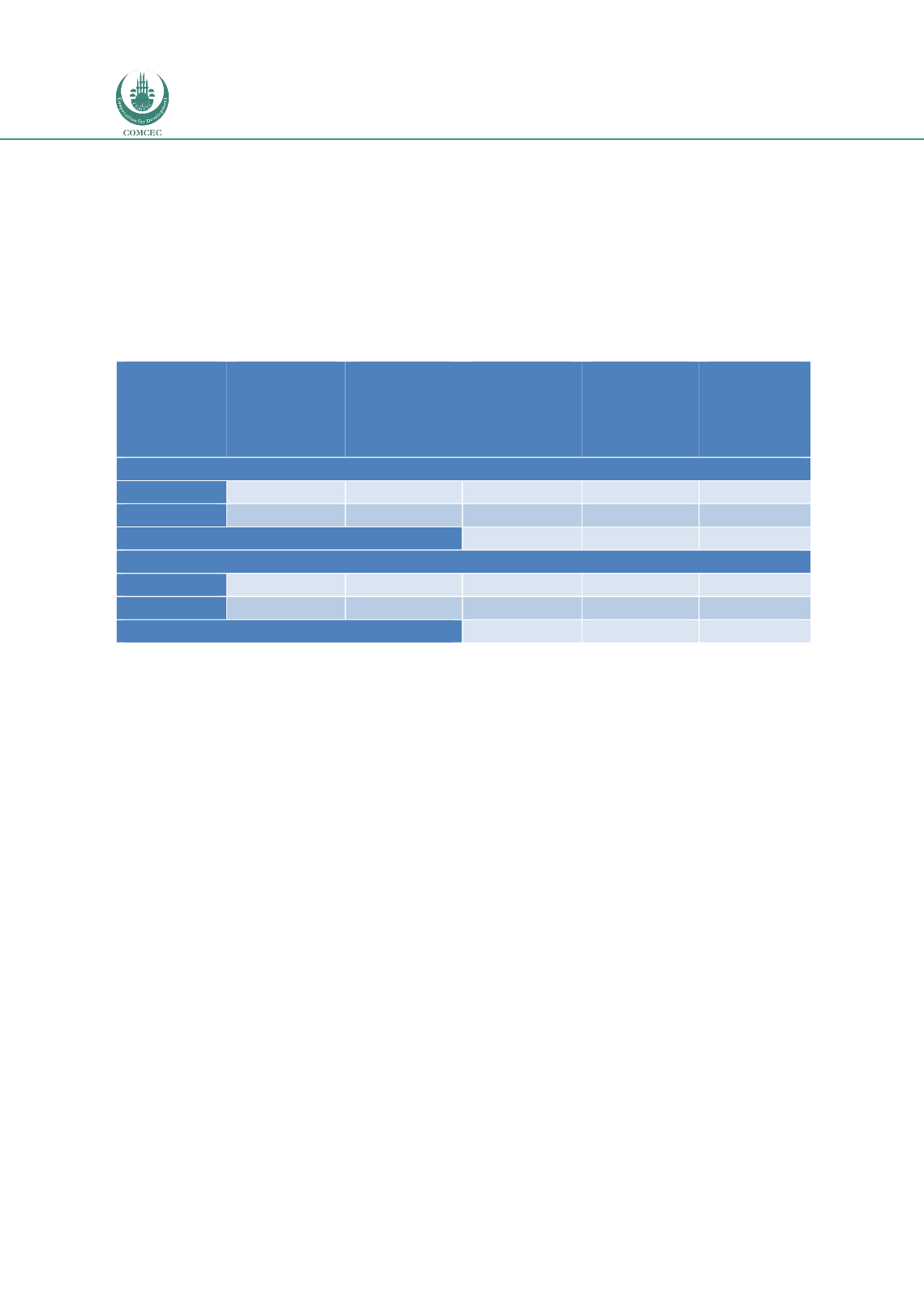

Table provides an estimation of losses in Uganda’s value chain

and their value.

Table 54: Estimated monetary value of annual quantitative PHL in Uganda’s dairy value

chain (in US$)

Stage in the

value chain

Quantity of

milk

(tonnes)

Postharvest

losses (PHL)

(%)

Quantitative

PHL

(tonnes)

Unit Value

(US$/ tonne)

Value of

Annual

Losses

(million

US$)

High loss scenario (2012 production, FAOSTAT)

Production

1,207,500

6%

72,450

187

13,548,150

Marketing

784,875

21%

164,824

187

30,822,041

Total

237,274

187

44,370,191

Average loss scenario (estimated 2015 production, marketing, and loss figures)

Production

1,400,000

3%

42,000

187

7,854,000

Marketing

910,000

10%

91,000

187

17,017,000

Total

133,000

187

24,871,000

During the rainy season milk losses reportedly more than double because, on the one hand,

production increases, whilst, on the other hand, milk collection is constrained due to poor road

conditions. It is estimated that during the wet season up to 42.8% of milk produced remains on

the farm unsold (FAO/ILRI, 2005), thereby leading to forced consumption by humans (e.g.

farmers family, neighbours). In particular, this is likely to affect producers in more remote

villages.

The same study (FAO/ILRI, ibid) states that along the milk supply chain, up to 18% of milk is

lost through spillage and spoilage.

Masembe Kasirye (2003) found that milk losses at the milk collection centres (MCC) are lower

in areas where the quality of raw milk is more controlled if it enters the formal sector, as

opposed to the lack of control and poorer quality of milk sold in the informal market. Whilst

most collection centres in urban/peri-urban areas have electrically-operated coolers, other

collection centres (i.e. mainly those in remote areas) often lack electricity and cannot easily

cool their milk. In this context, according to Masembe Kasirye, F (2003), spoilage losses

associated with electricity failure average 2% of incoming milk per day.

In parts of the country where there is a lack of marketing infrastructure, the quality of milk is

likely to be poor due to lack of quality control, lack of cooling facilities, and use of

inappropriate containers (e.g. plastic jerry cans which are difficult to clean). For example, in

Nakasongola 37% of the milk supplied during the wet season soured and was returned to the

primary vendor at the pooling centre, whilst the loss during the dry season due to souring was

much less (11%) (Masembe Kasirye, 2003). In comparison, in the South-West of the country

milk losses are lower which can be explained by the relatively controlled raw milk quality