Analysis of Agri-Food Trade Structures

To Promote Agri-Food Trade Networks

In the Islamic Countries

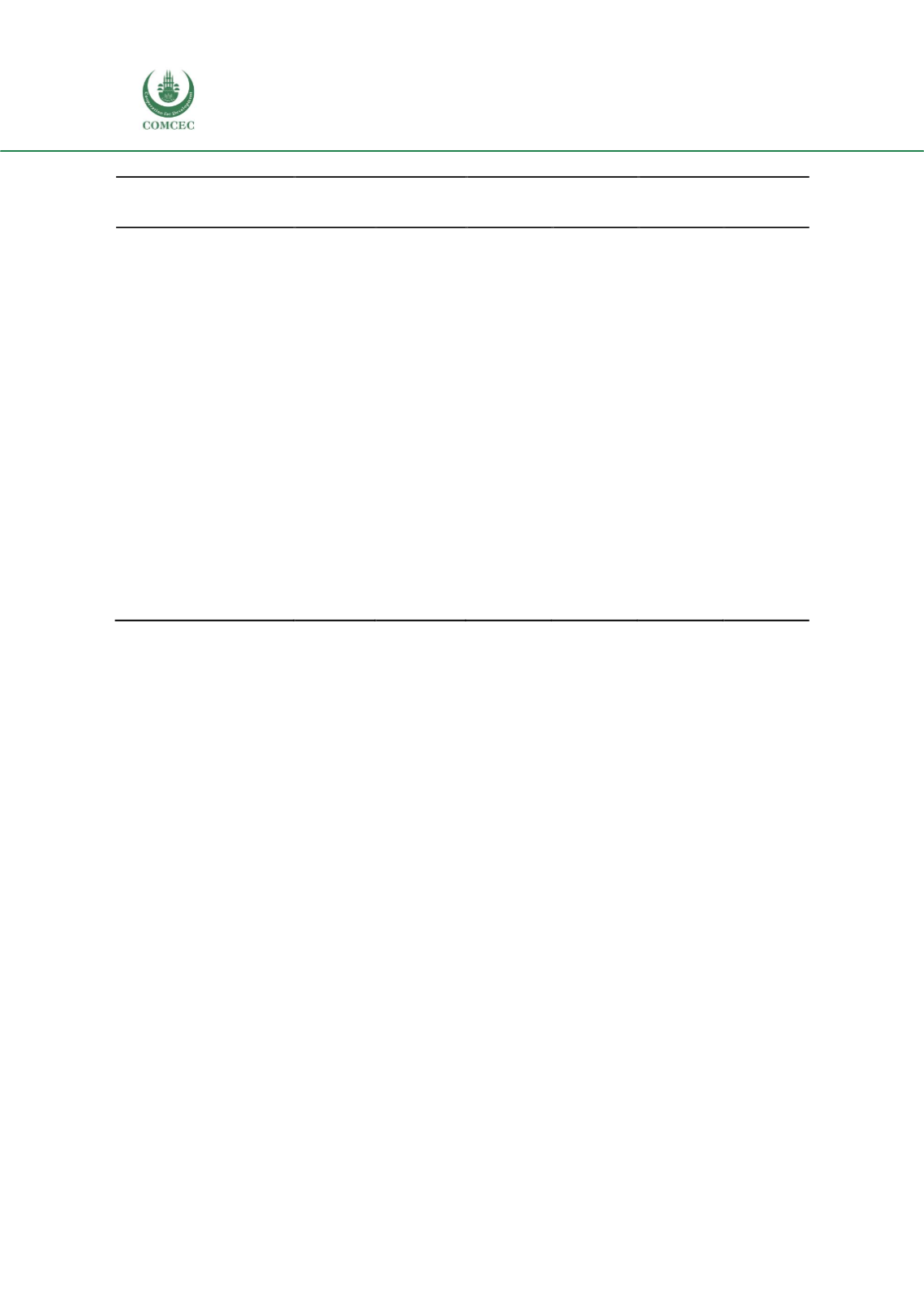

55

Table

13:

PreferenceMargin by Importing Group and Product, 2005 and 2016, Percent of MFN Rate

African Group

Arab Group

Asian Group

2005

2016

2005

2016

2005

2016

Live animals

3.33

25.10

27.77

73.05

0.84

7.45

Tobacco

2.16

39.44

75.31

68.48

1.16

24.66

Oil seeds

0.00

36.84

59.85

43.20

0.98

6.92

Crude rubber

0.00

34.78

34.58

51.85

0.71

9.92

Cork and wood

0.00

23.91

39.45

50.05

11.42

23.81

Rice

0.00

25.55

75.26

77.57

0.00

23.95

Vegetables

0.00

27.14

51.05

43.60

0.63

21.23

Fruit and nuts

1.04

22.39

39.62

49.67

0.28

7.39

Coffee

0.00

19.27

49.61

43.55

6.11

28.17

Other edible products

0.61

21.66

60.74

59.35

1.04

14.38

Cotton

0.00

42.86

45.87

46.87

0.00

22.07

Bread products

0.00

20.63

50.14

52.35

0.37

23.56

Palm oil

0.00

33.69

35.67

40.31

0.00

5.61

Fish and crustaceans

0.00

28.40

51.26

33.77

0.86

18.47

Cocoa and chocolate

1.21

23.29

43.48

48.00

1.58

14.37

Rest of 06

0.00

18.37

51.71

51.80

1.91

10.96

Source: TRAINS via WITS.

This policy analysis shows that the dynamic towards regional integration, as embodied in the

rise of RTAs involving OIC members, has played a strong and fundamental role in shaping trade

flows. Over time, the effective difference in the restrictiveness of policies facing RTA partners as

compared with MFN policies has grown substantially. In combination with geographical

considerations and product features, this fundamental dynamic has reinforced the tendency of

intra-OIC trade to take place within, rather than across, regional groups. As such, the network of

RTAs among OIC countries has been a defining feature of the multiple networks of trade flows

that are now in evidence.

In addition to formal trade agreements involving OIC members, there is also the Trade

Preferential System (TPS) Among Member States of the OIC (TPS-OIC). The legal basis for this

system is fully in place, and the instruments have been ratified by the required number of

countries. However, before the preferences can take effect, it is necessary for members to submit

updated concession lists; as of December 2017, seven countries had done so. Preferential

arrangements like this can potentially boost trade with beneficiaries, but as with any

discriminatory liberalization, policymakers need to pay attention to the dual effects of trade

creation and trade diversion. The same is true of regional agreements. Policymakers should craft

schedules of concessions designed to maximize reliance on low cost suppliers, i.e. maximize

trade creation. Accompanying enhanced preferences with multilateral rate reductions is a good

way of minimizing trade diversion—and this would be in keeping with the progressive

liberalization of tariff rates referred to above.