Improving Agricultural Market Performance:

Developing Agricultural Market Information Systems

91

farmgate level. Consequently, distribution margins increased and producer margins were

squeezed. In addition, it was noted that most of the rural aggregators (“bicycle traders”) failed

to pay a quality premium at the farmgate leading to the quality of Ugandan exports being

compromised and the country losing out on quality premiums. The government also disengaged

from setting administrative prices for the export crops leading to increased price uncertainty.

Within the domestic agricultural markets, part of the reforms included the disengagement of

government from setting guaranteed minimum prices and enforcing quality standards. As a

result the marketing systems for grains experienced price uncertainty, quality variability and

lengthening of the chain (Onumah and Nakajjo). A recent study by IFAD (2015) estimates that

farmers on the average lose over US$260 million per year as a result of their limited capacity to

mitigate volatility in output prices. This is more than double the estimated annual losses due to

crop pests and diseases and also more than six times the estimated annual losses due to the

incidence of drought. The same factors also limit the capacity of Uganda to exploit huge regional

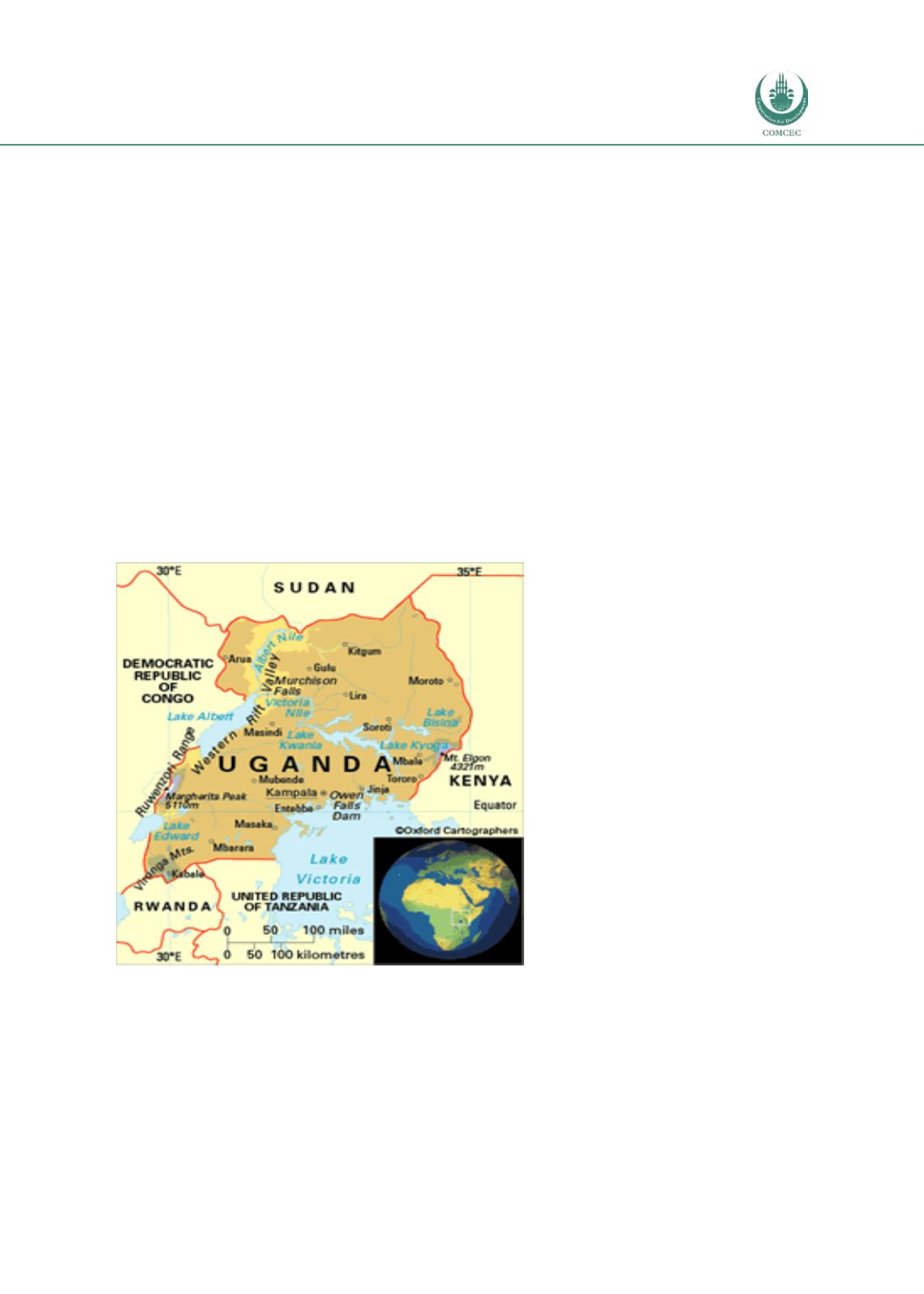

agricultural exports potential. Most of the countries sharing borders with Uganda (See Figure

38) have significant food deficits, especially for staple grains and oilseeds. Top among these is

maize into Kenya and South Sudan as well as beans and oilseeds into Rwanda and the

Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Figure 38: Map of Uganda and Border Countries

In addition to the challenges in the agricultural output markets, IFAD (2015) also notes that the

quality and reliability of agricultural inputs marketed Uganda became highly uncertain when

government discontinued direct inputs distribution and allowed a private inputs marketing

system to emerge. These factors contributed to under-performance of the agricultural of the

sector over the past two decades, with its growth stagnating at about 2% per annum (Mwesigye

et al., 2017). This growth rate is way below the annual growth target of over 5% set by the

National Development Program (NDP) for effective poverty reduction in the country (IFAD,