Forced Migration in the OIC Member Countries:

Policy Framework Adopted by Host Countries

136

solis); only refugees who have been married to a Ugandan citizen for at least five years, or

have resided in Uganda for at least 20 years (and speak one of the official languages of

Uganda) can naturalize.

32

But in practice, refugees who meet these conditions have

encountered practical barriers to naturalization: for example, local officials who are

unfamiliar with the law and procedures for refugees naturalizing.

33

Meanwhile, Uganda’s national IDP policy’s central objective is to ensure IDPs have the same

rights, freedoms, and treatment under the law as other Ugandan citizens.

34

This includes

ensuring there are no restrictions on their freedom of movement (for example, by allowing

free movement in and out of camps, and improving security in the areas where IDPs live to

allow movement); replacing lost or destroyed documents; providing IDPs with shelter,

clothing, and food; and helping returnees access their land, or allocating them new land.

35

As

well as guaranteeing equal access to education services, the policy also requires the

government to create affirmative action schemes for IDPs to ensure they can attain the same

educational standards, and providing IDPs with psychosocial services.

36

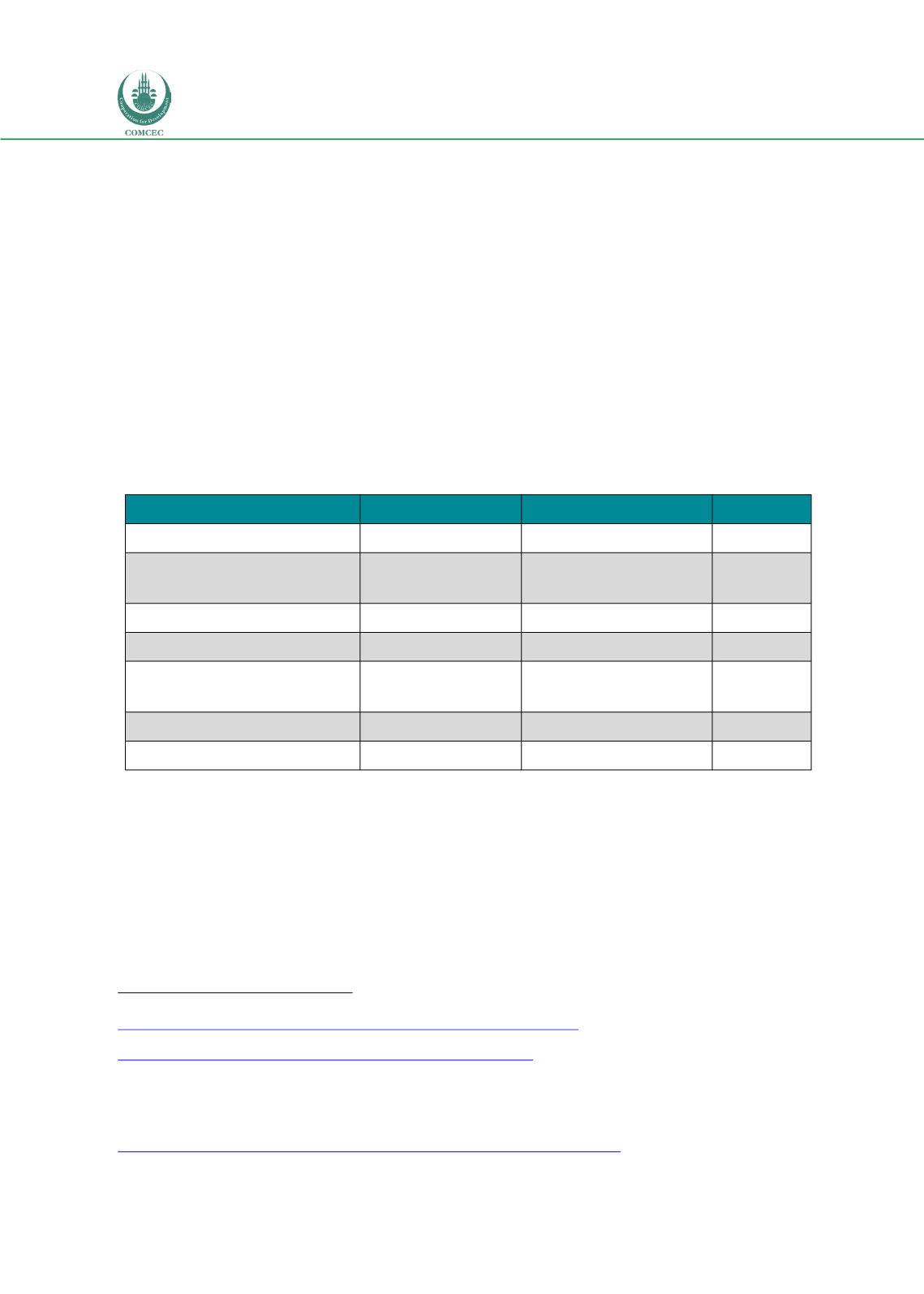

Table 12: The rights of refugees, asylum seekers, and IDPs under Ugandan law

Refugees

Asylum-seekers

IDPs

Permission to work

Yes

No

Yes

Permission to establish a

business

Yes

No

Yes

Own property

Yes

No

Yes

Freedom of movement

Some restrictions

Some restrictions

Yes

Access to public healthcare

services

Yes

Yes

Yes

Access to public education

Yes

Yes

Yes

Political participation

No

No

Yes

Note: Refugees are technically required to ask for permission from their settlement commandant before moving,

while asylum seekers can only access shelter and food in the settlements (though they can access these services

for up to three months elsewhere during the initial registration process).

In practice, full implementation of these policies—and, therefore, full access to the rights they

include—hinges on resources that are often lacking. Limited local government capacity and

limited funds, coupled with a reliance on external resources, all served to inhibit the

implementation of the national IDP policy.

37

Similarly, a lack of funding has hampered the

implementation of the 2006 Refugee Act and the accompanying Refugee Regulations of 2010.

32

The Uganda Citizenship and Immigration Control Act,

1999,

http://refugeelawproject.org/files/legal_resources/CitizenshipImmigrationact.pdf .33

Sam Walker, “Can Refugees Become Citizens of Uganda?” Refugee Law Project Briefing Paper July 2008,

http://www.refugeelawproject.org/files/briefing_papers/RLP.BP0803.pdf .34

Chapter 1,

The National Policy for Internally Displaced Persons,

2004.

35

Chapter 3,

The National Policy for Internally Displaced Persons,

2004.

36

Chapters 3.1.1 and 3.1.2,

The National Policy for Internally Displaced Persons,

2004.

37

Friedarike Santner, “Uganda’s Policy for Internally Displaced Persons. A Comparison with the Colombian Regulations on

Internal Displacement,”

International Law: Revista Colombiana de Derecho Internacional

22 (Jan/June 2013),

http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1692-81562013000100004 .