Risk & Crisis Management in Tourism Sector:

Recovery from Crisis

in the OIC Member Countries

127

insecurity and high-profile military presence were deterrents to less resilient market segments.

This was reflected in the decline in annual arrival figures, from560,000 in 2006 to 448,000 in 2009

(Table 5.4).

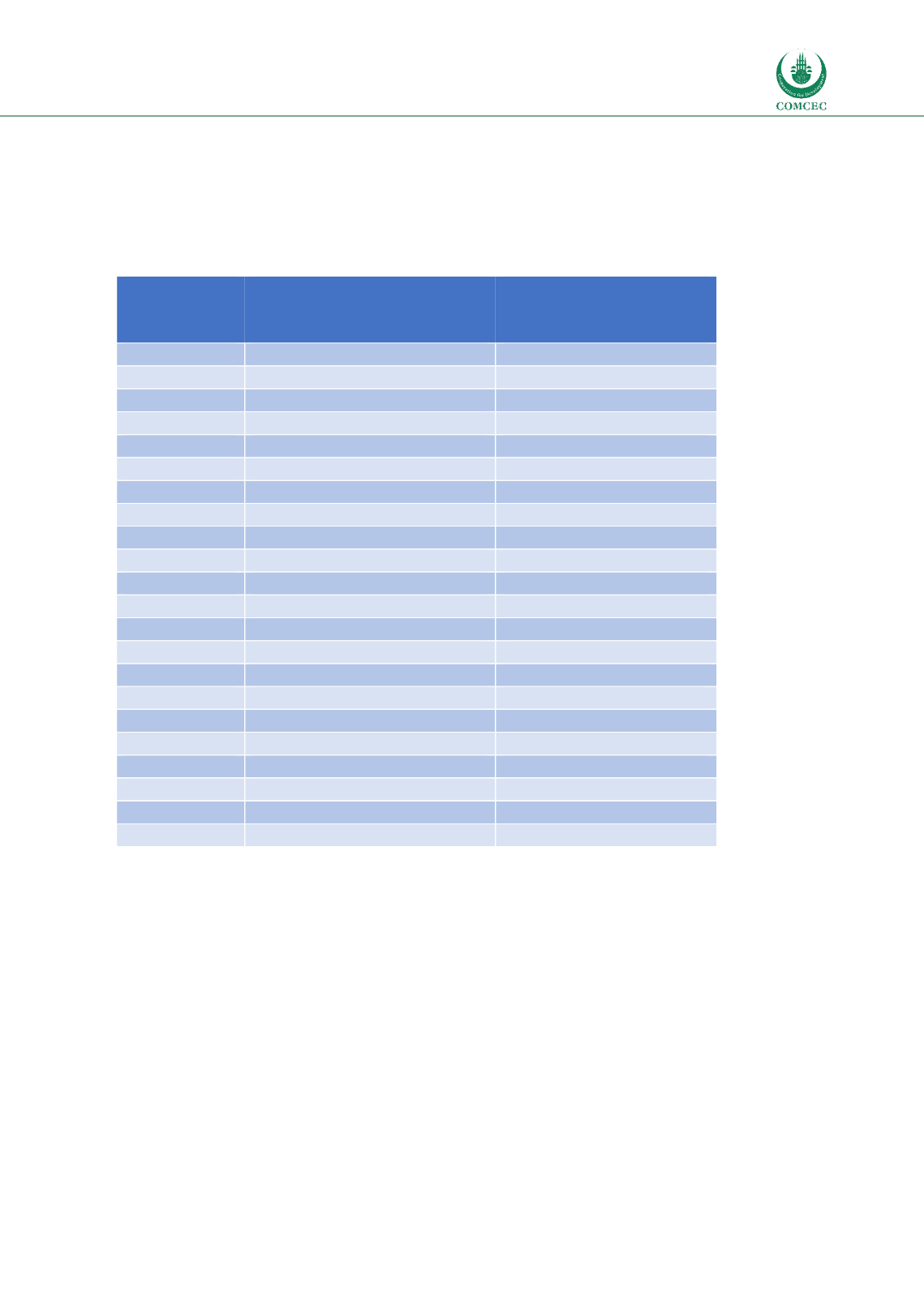

Table 5.4: International Visitor Arrivals and Foreign Exchange Earnings – Sri Lanka

Year

Tourist Arrivals (‘000s)

Foreign exchange earnings

(US$ Million)

1995

403

225.4

1996

302

173.0

1997

366

216.7

1998

381

230.5

1999

436

274.9

2000

400

252.8

2001

337

211.1

2002

393

253.0

2003

501

340.0

2004

566

416.8

2005

549

362.3

2006

560

410.3

2007

494

384.4

2008

438

319.5

2009

448

349.3

2010

654

575.9

2011

856

838.9

2012

1,006

1,038.3

2013

1,275

1,715.5

2014

1,527

2,431.1

2015

1,798

2,980.6

2016

2,051

3,518.5

Sources: Tourism growth trends, 1970-2016; SLTDA statistics and annual reports; UNWTO

Even apart from these obvious causes of sector under-performance and before the 2004 tsunami,

it was acknowledged that tourism to Sri Lanka was not fulfilling its potential in terms of its

contribution to foreign exchange earnings, numbers of tourists, and the diversity of market

segments. Some of the reasons for this will be discussed below, after an overview of structural and

market aspects are provided.

The principal government organisations concerned with tourism at the time of the 2004 tsunami

were theMinistry of Tourism and the Sri Lanka Tourist Board (SLTB), which report to the Ministry.

Other key institutions were the government-run Sri Lanka Institute of Tourism and Hotel

Management, and private sector associations such as the Tourist Hotels Association of Sri Lanka,

which works with the government on policy and with other trade sectors, and functions as a

marketing organisation. Several of the larger destinations also had their own associations: for

instance a stakeholder analysis at the west coast resort town of Hikkaduwa in 2007 found at least