Forced Migration in the OIC Member Countries:

Policy Framework Adopted by Host Countries

103

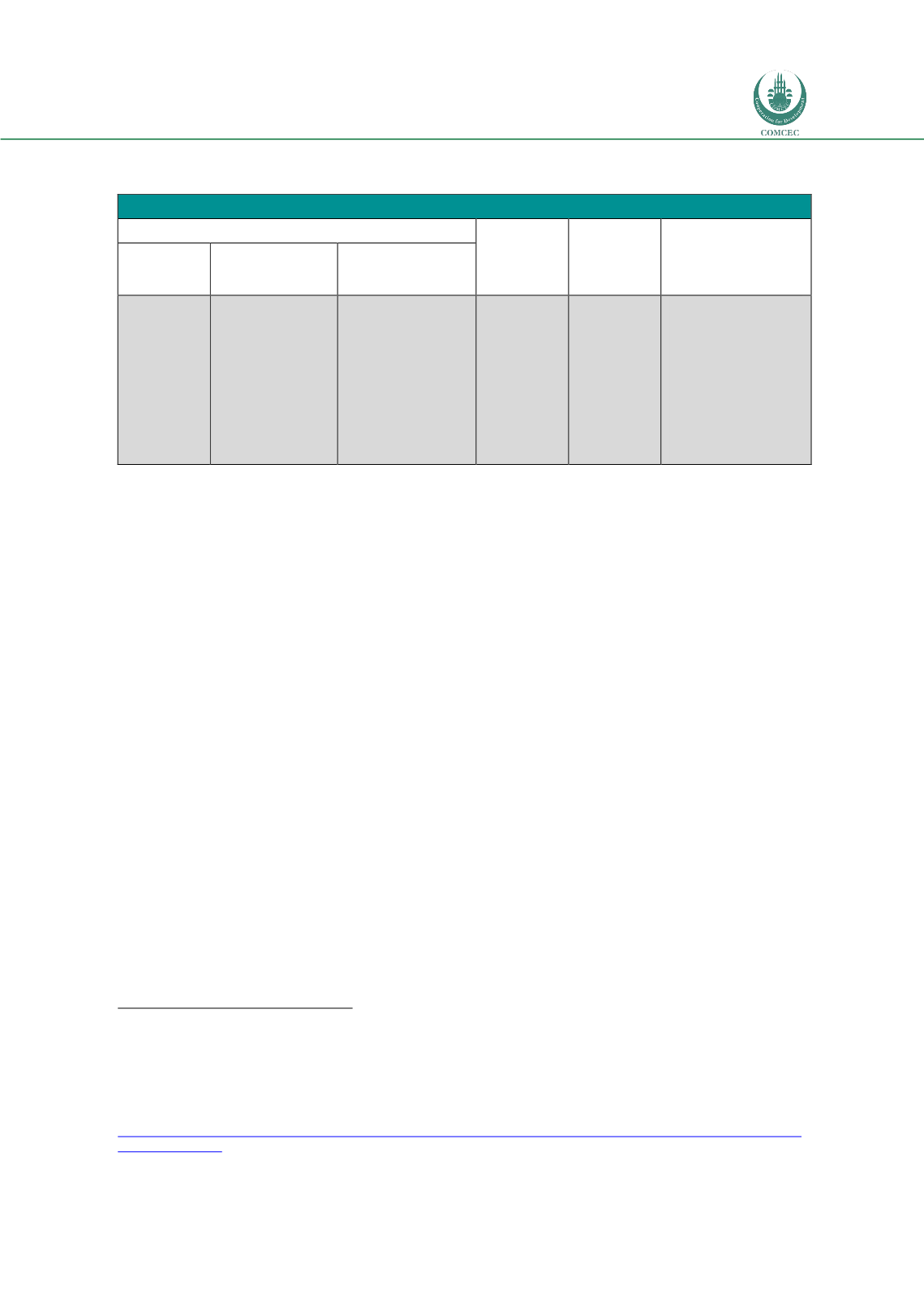

Table 8: School access rights and fees for refugee children

Access to Education for Refugees by Nationality

Palestinians

Syrians

Iraqis

Other

1948

Refugees

Ex-Gazans

Palestine

Refugees

from

Syria (PRS)

Free access

to

UNRWA

schools

Free access

to Jordanian

schools,

as

nationals

Free

access

to

UNRWA schools

Charged foreigners’

fee (USD 56 for

primary school and

USD

85

for

secondary school)

to access Jordanian

schools

Free

access

to

UNRWA schools

Charged foreigners’

fee (USD 56 for

primary school and

USD 85 for secondary

school) to access

Jordanian schools

Enrollment

fees waived

by

government

Enrollment

fees waived

by

government

Charged foreigners’ fee

(USD 56 for primary

school and USD 85 for

secondary school) to

access

Jordanian

schools.

For

Somalis

and

Sudanese,

fees

subsidized by UNHCR

and NGOs

Documentation can be another challenge. To register for school, children are required to have

a valid UNHCR asylum seeker card and Syrians must have registered with the Ministry of the

Interior. In addition, children are generally required to supply documents from their previous

school to attest to their education level, although the Ministry of Education has eased this

requirement as refugee children were frequently unable to supply this documentation.

224

Other policy and practical barriers may prevent students from enrolling in or attending school

among both Syrian and Iraqi families.

225

Perhaps most critically, children who have been out

of school for more than three years are not allowed to enroll in the formal school system,

potentially creating a barrier for refugee students who may have experienced lengthy

disruptions to their education. Moreover, support for students with non-traditional education

trajectories is limited in Jordanian schools, and few opportunities exist for children who are

behind to catch up with their peers. This challenge is exacerbated by the fact that students are

only allowed to enroll at the beginning of the school year, and as a result, children who arrive

during the year must often wait until the following fall to begin school. Families have also

reported that a lack of transportation and costs for schools supplies and uniforms can be

prohibitive, particularly outside of camps.

In addition to efforts by the government to remove some formal obstacles to education like

fees, international agencies and donors have stepped in to provide assistance. For example,

the UN and international NGOs have undertaken outreach campaigns to inform children and

families how to enroll in school, and have supported “catch up” programs for students who

have been out of school for a prolonged period.

226

Most such efforts have, however, focused on

Syrians, and much less attention has been paid to the situation of smaller refugee communities

in Jordan. UNHCR and NGOs offer assistance to cover schooling costs for Sudanese and Somali

refugee children,

227

but little is known about their access to education or enrollment and

224

Communication from ARDD-Legal Aid, May 2016.

225

Barriers here have been cited in surveys and assessments among both Syrian and Iraqi families in Jordan. See Hart and

Kvittingen,

Tested at the Margins,

See and RAND Europe, “Evaluating UNICEF's Emergency Education Response Programme”

and

226

RAND Europe, “Evaluating UNICEF's Emergency Education Response Programme”

227

ARDD-Legal Aid,

Putting Needs Over Nationalities

, p7; UNHCR, “Jordan: UNHCR Operational Update, October 2015,”

updated October 31, 2015,

http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/UNHCR%20Jordan%20Operational%20Update%20October%202015%20FINAL.pdf