Governance of Transport Corridors in OIC Member States:

Challenges, Cases and Policy Lessons

21

current corridor performance, identify bottlenecks and define room for improvements. However, in

many cases, the initial objectives are not so clearly defined, nor are they based on advanced analytical

performance techniques. A detailed corridor performance assessment could be performed in later

stages when objectives are defined in the specific. Yet, data on corridor performance can be used to

gain support from a variety of stakeholders in the early stages leading up to the first agreement.

As transport is such an intrinsic part of the functioning of society, objectives often go beyond the

transport system itself. Transport infrastructure connects regions, economic activities and people.

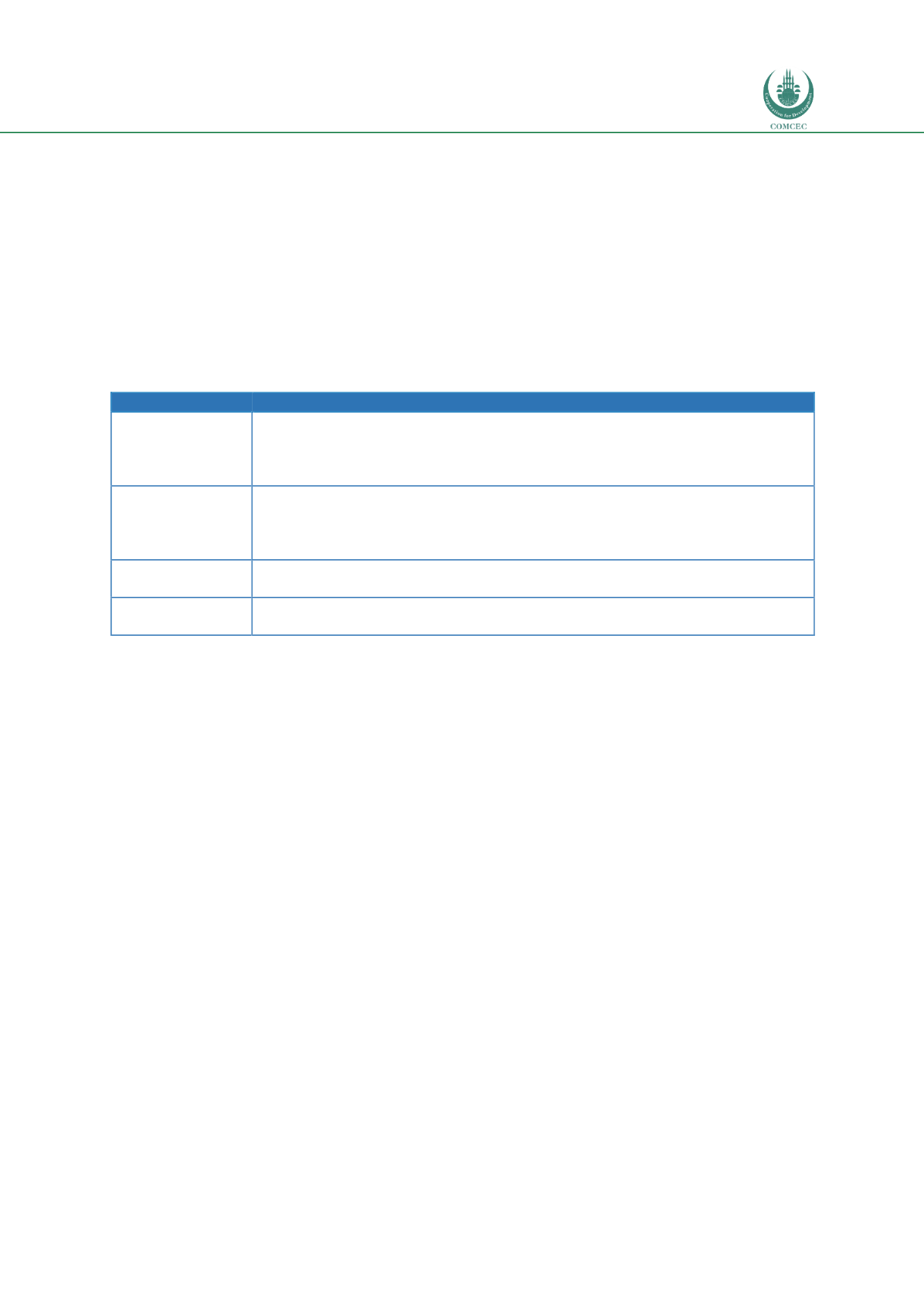

Table 2.2 shows the various secondary objectives related to social, political, environmental and

economic issues that can be achieved when developing transport systems.

Table 2.2 Secondary objectives related to the development of transport systems

Dimension

Objectives

Social

Facilitating access to social services such as welfare or healthcare by

increasing the mobility of people;

Contributing to food security in Africa (Kuhlmann, Sechler & Guinan, 2011);

Social cohesion in EU (Aparicio, 2017).

Political

Governments can achieve political goals through transport, such as job

creation, regional development, or the creation of a channel for political

dialogue between nations;

Establish political dialogue in the Western Balkan (SEETO).

Environmental

Transport has a significant impact on environmental issues related to public

health, noise pollution and water and air quality.

Economic

Transport facilitates the growth of economic activities and the economic

competitiveness of the participants.

Source: based on Rodrigue, Comtois, & Slack (2006).

Transport corridors are included in national strategies and plans

Objectives are defined during the knowledge exchange phase, in which the various stakeholders get

together and identify a common interest regarding the development of the transport system. Once the

stakeholders find consensus, the process of drafting an agreement begins. Such agreements differ in

terms ambition and extent to which they are binding, and may range from a Memorandum of

Understanding (MoU), intending a common line of action without legal commitment by its signees, to

international treaties regarding various commitments and requiring domestic authorization. Each of

the seven corridor governance aspects may be included in the agreement to varying levels of detail.

Hence, the extent to which the plans on corridor development are incorporated in national strategies

depends on the arrangements between the nations. MoUs are not binding, and merely indicate a

willingness to do something. There are no consequences for non-compliance. Treaties on the other

hand are binding and need to be incorporated in national strategies. The ambition outlined in the

objectives determines the scope and depth of the rest of the governance aspects.

2.2.2

Legal framework

Legal basis

Once there is a consensus between the different stakeholders on the objectives and management of

the corridor, the process of creating a legal basis begins. Legal instruments are binding (to various

degrees) and commits countries to carry through transport reforms. The legal framework takes form

as an agreement between the participants, defined by Kunaka and Carruthers (2014, p. 74) as: